Janáček – Jenůfa

Jenůfa – Laura Wilde

Kostelnička – Eliška Weissová

Laca Klemeň – Clay Hilley

Števa Buryja – Dovlet Nurgeldiyev

Grandmother Buryja – Janina Baechle

Mill Foreman – Tigran Martirossian

Mayor of the Village – Kim Han

Karolka – Na’ama Shulman

Barena – Claire Gascoin

Mayor’s Wife – Olivia Warburton

Maid – Anna-Maria Torkel

Jano – Yeonjoo Katharina Jang

Chor der Hamburgischen Staatsoper, Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg / Tomáš Netopil.

Stage director – Olivier Tombosi.

Staatsoper, Hamburg, Germany. Saturday, January 13th, 2024.

As always, it’s a pleasure to be back in beautiful Hamburg and to attend a show at the equally beautiful Staatsoper. Tonight was a revival of Olivier Tombosi’s 1998 production of Jenůfa, the thirty-fifth performance of this staging in the house. I actually saw it back in 2016 in San Francisco, and discussed it at length then. Of course, seeing it in the theatre that it was conceived for brought a different perspective, which I will discuss shortly. The main attraction of this revival was the presence of the great Evelyn Herlitizus as the Kostelnička, reunited with Tomáš Netopil in the pit, with whom she gave a gripping account of the role in her prise de rôle in Amsterdam, back in 2018. Unfortunately, Herlitzius withdrew at short notice from the run, and was replaced by the experienced Eliška Weissová. The title role was taken by the young US soprano Laura Wilde, herself a replacement for the originally-cast Natalya Romaniw, who was a lovely Jenůfa in Rouen last year.

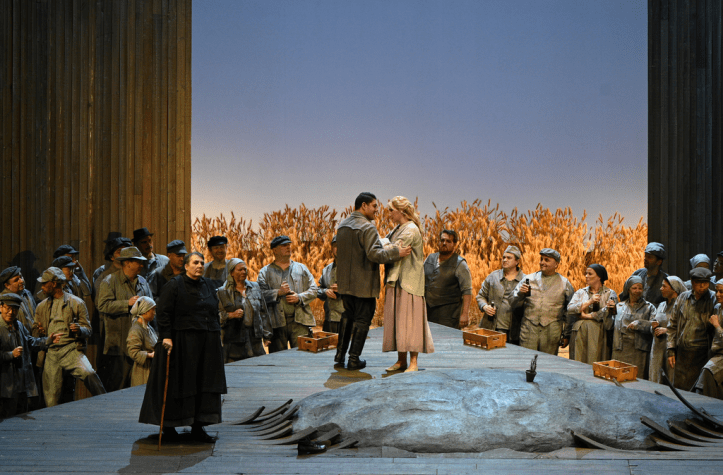

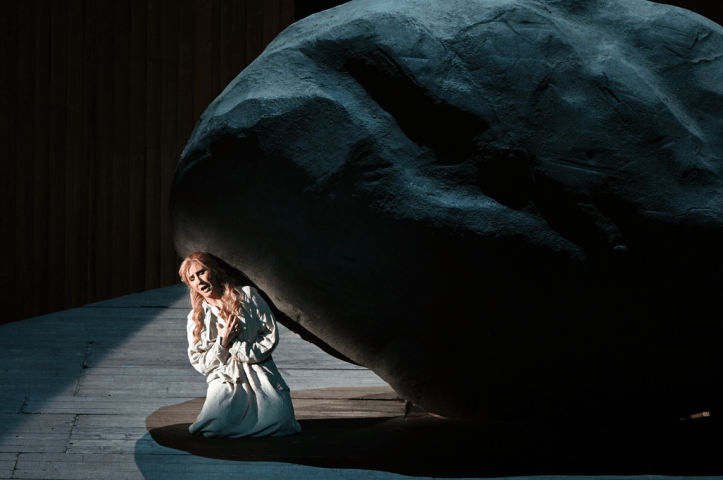

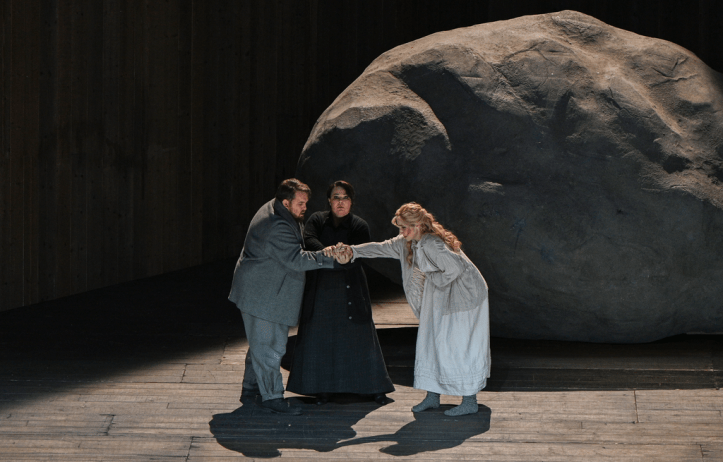

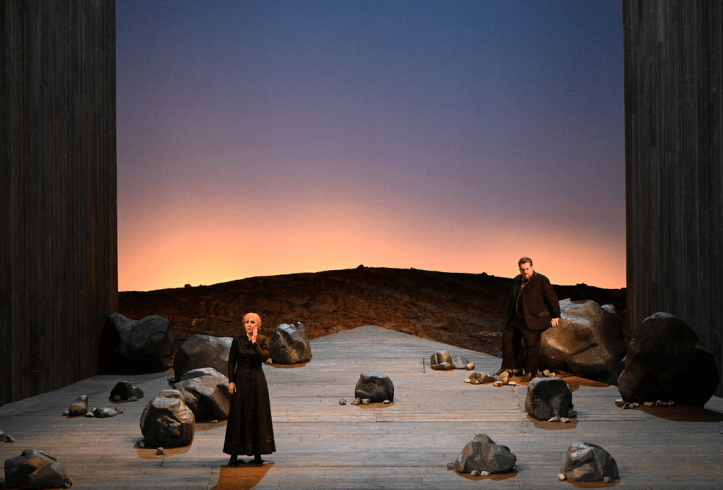

What struck me about Tombosi’s staging this time around is the significance of the stones that appear in the set. In Act 1, a large stone seems to want to penetrate the floor; in Act 2, it dominates the set; while in Act 3, it’s shattered into pieces. In so doing, Tombosi highlights the huge weight of the events of the plot and their implications for the characters involved. Having the set of Act 2 dominated by the huge stone placed centre-stage, seems to portend how monumental both the birth of Jenůfa’s baby and the child-murder committed by the Kostelnička were. And yet, in its symbolism, it seems rather heavy-handed. That said, I did find that the setting for Act 2, with the wooden set closing in at the back seemingly reflecting the wood of the Staatsoper auditorium, to be a visually striking touch. As a revival, tonight directed by Marie-Christine Lüling, one might expect the characterizations to be perhaps not as detailed as in a new production. This I felt was the case with the chorus, who were simply parked on the stage and invited to randomly gyrate in the celebrations of Act 1. There was also a considerable quantity of outstretched hands and singing to the front. Still, it’s an efficient framework for the action, but I did long for the visceral realism of Calixto Bieito’s Stuttgart staging that was revived in Rouen last year.

That sense of tentativeness also found its way into Netopil’s conducting. His reading in Amsterdam was absolutely thrilling, indeed it’s one I return to often since I was able to download the radio broadcast of the run. Here, he obtained some extremely classy playing from the Hamburg orchestra. The brass, in particular, had a wonderfully distinctive tone and the clarinets were nicely folksy in their introduction to Act 3. The strings in Act 2 really managed to portray those cold, icy winds that penetrated into the house. Attack throughout was unanimous and, other than a few small brass splits towards the end of the evening, and a couple of wrong entries in the violins, the quality of the playing was not in doubt. And yet, I found Netopil’s reading this time around to be rather saggy and lacking in momentum. In Act 2, I missed this sense of inexorably building tension. Instead, Netopil’s direction felt tentative. This could, of course, be due to the difference in rehearsal time between a premiere and a revival such as this. That isn’t to say that Netopil’s direction lacked insight. I was particularly struck by the way that the lower strings seemed to echo that insistent xylophone motif in the closing scene, this time finding calmness and warmth. It’s just that, perhaps, my expectations were set too high after what he had achieved in Amsterdam.

Wilde sang Jenůfa in a bright soprano with admirably well-schooled musical instincts. She has clearly studied the idiom and understands how the music should go. Her soprano is rather narrow in sound, tending to brittleness at the top, and chalkiness at the bottom. There were moments when she brought out an agreeable creaminess in the tone, yet the phrasing in the prayer was a little choppy, perhaps getting carried away with the emotion. To my ears, Wilde sounds more like a Susanna or a Despina at this point in her career, due to the narrowness of the tone, but she’s very young and has time to grow into this role, and she’s an honest actor. She certainly sang with dignity and gave a good account of herself.

Weissová gave us a massive wall of sound as the Kostelnička. The voice is huge. I’m not going to claim that it’s pretty, but she’s certainly capable of significant volume. The registers aren’t quite integrated, though Weissová made use of a very juicy chestiness. Her soprano is rich in tone, but does tend to lose the core on the rare occasions that she pulled back on the volume. Her technique is inconsistent, suggesting that the support isn’t quite lined up to sustain that monumental sound, audible through how she tapered off towards the end of long phrases. As the only native Czech singer in the cast, I had hoped that Weissová would make more of the text, but her singing felt rather old school statuesque on the whole. She did rise to an extremely powerful moment as she contemplated murder, and her final phrase of Act 2 was suitably hair-raising, resorting to a frightened sprechgesang. Still, if Weissová could strengthen the support she could become a very exciting and useful artist.

This was my first occasion hearing Clay Hilley and here is another very exciting talent. His tenor is wonderfully beefy, but also bright in tone. The voice is even from top to bottom, but he’s also able to scale back the sound and sing with real delicacy. He also coloured the text, using the words as the starting point for the line. Without doubt a singer to watch. Dovlet Nurgeldiyev coped very well with Števa‘s challenging tessitura, singing with ease on top where so many before him have sounded in pain, and was an appropriately extrovert stage presence. The remaining roles reflected the quality one has come to expect here. Tigran Martirossian’s bass was appropriately warm in tone as the Foreman, while Kim Han was an extrovert Mayor. Yeonjoo Katharina Jang gave us a prettily sung account of Jano’s music. Some of the other soprano and mezzo roles weren’t always audible from my seat in the centre of the Parkett. Eberhard Friedrich’s chorus sang with discipline and focused tone. Above all, it was Janina Baechle’s grandmother who brought humanity to the staging. She sang with warmth and generosity throughout.

Tonight, we got a decent repertoire performance of this always fascinating work. Tombosi’s staging did what it needed to do, even if the symbolism feels heavy-handed now – not helped by the fact that it required two intermissions, dragging the evening out. The singing was admirable – Wilde showed some promise in the title role, Weissová was a force of nature, while Hilley was an extremely impressive Laca. The quality of the orchestral playing was excellent, although I did find Netopil’s conducting to lack the coruscating drama he has previously brought to the work. The audience responded at the close with warm applause, with particularly loud cheers for Wilde, Weissová and Hilley.

[…] year started with Jenůfa in Hamburg, with Eliška Weissová demonstrating some considerable volume as the […]