Tchaikovsky – Pikovaya Dama (Пиковая дама)

Herman – Brandon Jovanovich

Count Tomsky – Roman Burdenko

Prince Yeletsky – Boris Pinkhasovich

Chekalinsky – Kevin Conners

Chaplizki – Tansel Akzeybek

Surin – Bálint Szabó

Narumov – Nikita Volkov

Master of Ceremonies – Aleksey Kursanov

Countess – Violeta Urmana

Liza – Asmik Grigorian

Polina – Victoria Karkacheva

Governess – Natalie Lewis

Masha – Daria Proszek

Kinderchor der Bayerischen Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor / Aziz Shokhakimov.

Stage director – Benedict Andrews.

Bayerische Staatsoper, Nationaltheater, Munich, Germany. Saturday, February 10th, 2024.

Performances of Pikovaya Dama seem to have been proliferating over the past two years. Having waited a long time to see the work live, since 2022 I have seen four productions: at the Scala, in Brussels, València, and now Benedict Andrews’ new production at the Bayerische Staatsoper, under the musical direction of Aziz Shokhakimov. Having opened a few days ago, this evening’s performance was livestreamed on the theatre’s website. The house chose to run the first two acts together, placing the intermission after Act 2. Those watching at home will have at least been able to stretch a little, though for those in the theatre it was somewhat hard going on the sitzfleisch.

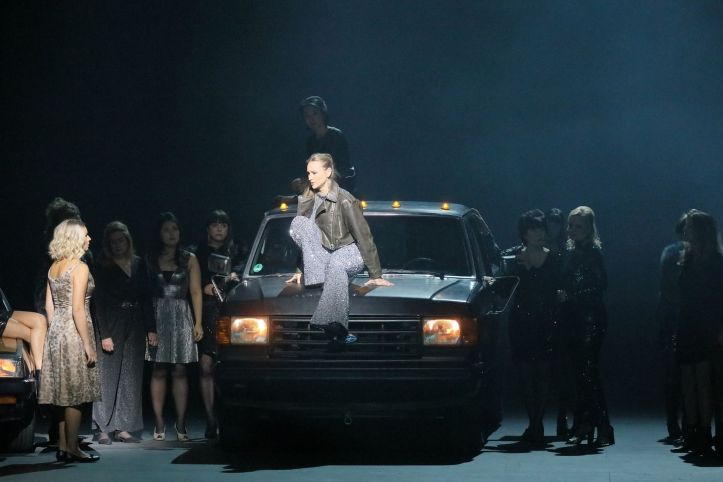

It did feel that losing the intermission between Acts 1 and 2 was an oversight, since Andrews’ staging does give a lot to think about. The main reason for this being that one is constantly wondering what is going on, and what are the implications of what one sees. Andrews’ staging is a succession of images. He seems to have been inspired in his stage pictures by the work of Calixto Bieito, whether in the chorus constantly emerging from the back of the stage, the use of close-up films of the principals on the front curtain between scenes, or the sparkling jumpsuit worn by Polina. Not to mention the girls entering on a convoy of automobiles in Act 1, scene 2, undoubtedly a nod to Bieito’s much-travelled Carmen.

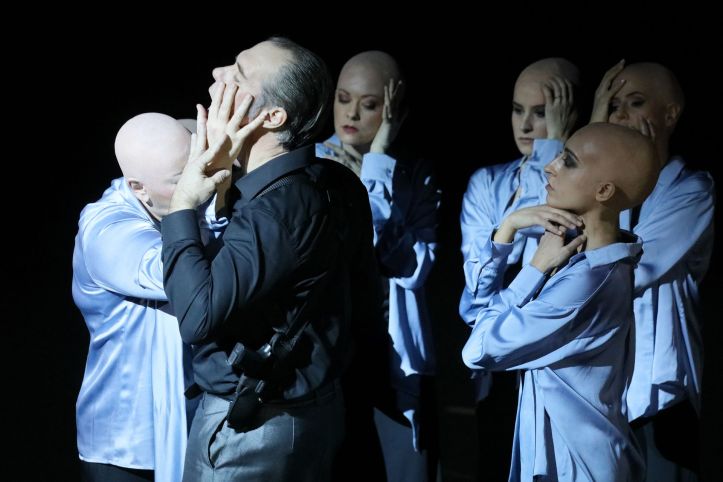

Yet where Bieito’s strength is in opera that shows deep empathy with the characters and pushes an audience to feel, it felt that Andrews’ visuals simply served to overshadow the performances of the principals, who were drowned out by the visual ‘noise’ surrounding them. That isn’t to say that some of Andrews’ images weren’t interesting. Populating the Countess’ boudoir with doubles of her, seemingly emphasizing Herman’s insanity was striking. Or the scene at the Winter Canal, the stage populated with a bridge full of urban lampposts, seemingly pointed to a world of film noir. Liza’s suicide was definitely impressive as she threw herself from said bridge. Not to mention, Herman alone in his barracks, here in a strip club, surrounded by a group of scantily-clad danseuses limbering up for a night working the poles. It’s just that Andrews’ staging lacked narrative clarity, made it difficult to understand any sense of time or place, or even motivation for the characters. It didn’t give us a context for us to understand why what we saw happened. That may have been the point. Perhaps Andrews wanted to give us a world of dreams and insanity, where nothing made sense. In that respect, he succeeded.

Shokhakimov led an orchestra on excellent form. The quality of the playing reflected what one would expect at this address. The clarinets, in particular, had real character. The strings alternated between muted duskiness and a thick-pile carpet of sound. I did find Shokhakimov’s tempi to be a bit on the slow side – Yeletsky’s romance threatened to come to a halt. Above all, I missed a sense of being able to bring out the deeper layers of the score, to make it so much more than a straight reading of notes on a page. I definitely missed the dynamism that James Gaffigan brought to the score in València, for instance. The chorus, prepared by Christoph Heil, had a very good evening. The sopranos and mezzos sang with decent blend, while the tenors and basses brought a richness of tone and impeccable tuning to their closing chorus. Not to mention the spectacularly resonant basses descending to the sepulchral depths.

Brandon Jovanovich is a singer I always look forward to seeing. Indeed, I was very much looking forward to seeing his Herman this evening. Unfortunately, it seems that Jovanovich was a bit out of sorts tonight. He was utterly valiant in his vocalism and acting, throwing himself into Andrews’ staging with seemingly unlimited energy, dispatching some very complex choreography in the masked ball scene. Vocally, however, his tenor sounded grey and colourless, the top seemingly disconnected from the remainder of the voice. He didn’t crack, but I spent the evening worried that he would. His energy and dedication inspired admiration, but I very much hope that the dryness of tone and effortful production are the products of a temporary and unannounced indisposition.

Asmik Grigorian’s Liza is a known quantity from the performances at the Scala two years ago. She is a staggering actor. Her Liza seemed to be aware of Herman’s obsession from the very beginning, yet became obsessed in her own way with Herman, seemingly happy to look past his obsession with the Countess and the cards. It did feel that Grigorian was overshadowed by the visuals, frequently acting by contorting her body at the front of the stage with much effort, to try and give meaning. Vocally, her soprano had that familiar pearly steeliness, she managed to sustain the lines well, even when having to lie on her back in her opening number. I did find the top to be a bit tight tonight, lacking in bloom and spin. Her repertoire has been focused on the big, high-lying roles and I hope these are not starting to take their toll. Still, she was vocally fearless and utterly determined throughout.

Violeta Urmana brought her decades of stage experience to the role of the Countess. Her mezzo still has genuine beauty in the middle, as she recalled her days in Paris. When she reappeared as a ghost, she pulled back all colour from the tone, giving it a pallid silkiness that was extremely haunting. She also made use of a generous chestiness, that was rich and full. Urmana was absolutely gripping, displaying an absolute mastery of vocal colour. Boris Pinkhasovich managed to sustain his celebrated romance well at the extremely slow tempo it was taken at. His baritone seems to defy gravity, with a remarkable ease on high. He also has an elegant line. Victoria Karkacheva’s Polina displayed an agreeably warm mezzo, genuine legato and evenness throughout the range.

In the remainder of the cast, Roman Burdenko was an extrovert Tomsky, firm of tone, making much of the text as he recounted the legend of the Countess. The smaller roles reflected the quality one expects from this house. Kevin Conners and Bálint Szabó were active presences as Chekalinsky and Surin, with a characterful tenor and rustic bass accordingly. A very welcome find was Natalie Lewis as the Governess, the warmth and richness of her mezzo promising a bright future, while Daria Proszek gave us a prettily-sung Masha in a dusky mezzo.

Musically, there was a lot to appreciate in tonight’s Pikovaya Dama, although there were also considerable reservations. I very much hope that it was a temporary indisposition that explains Jovanovich not sounding on top form. Grigorian’s Liza was thrilling in her fearlessness, while Urmana’s Countess was positively Shakespearian in her dramatic insight. The remainder of the singing was decent, as was the orchestral playing and choral singing. That said, the evening was let down by some prosaic conducting and a staging that seemed dramatically inert, lacking in narrative insight and context, and left me cold. That said, the evening was received with a very warm and positive reception from the audience, so it’s clear that it was appreciated by a significant proportion of the public.

.