And so, we come to the end of another year of music. This year has seen me enjoy live performances from as far afield as Dresden to Buenos Aires, and Hamburg to São Paulo. Reflecting on the year just gone has reminded me that it was a spectacular year of music in so many respects.

As always, one of the biggest pleasures I have is watching young artists as they grow into their careers. We have much reason to be pessimistic about the future, but the truth is the pipeline of young talent coming through is very encouraging. The young Flemish conductor, Martijn Dendievel, in a Don Giovanni in Bologna reminded us that he’s a conductor of elegance and taste. In Parma, at the Festival Verdi, I was thrilled by Diego Ceretta’s conducting of La battaglia di Legnano, where he established swift tempi and encouraged ornamentation, essential in early Verdi, while Marina Rebeka was a sensational Lida and gave us a singing lesson. In Milan, Vincenzo Milletarì gave us a glorious Suor Angelica, demonstrating a profound understanding of the Puccinian style. In Rome, I also saw a Sonnambula that was fabulously sung, with Ruth Iniesta bringing so much emotion to the role of Amina, Marco Ciaponi a tenor of exciting promise as Elvino, and Manuel Fuentes bringing his warm, healthy bass to Rodolfo’s music.

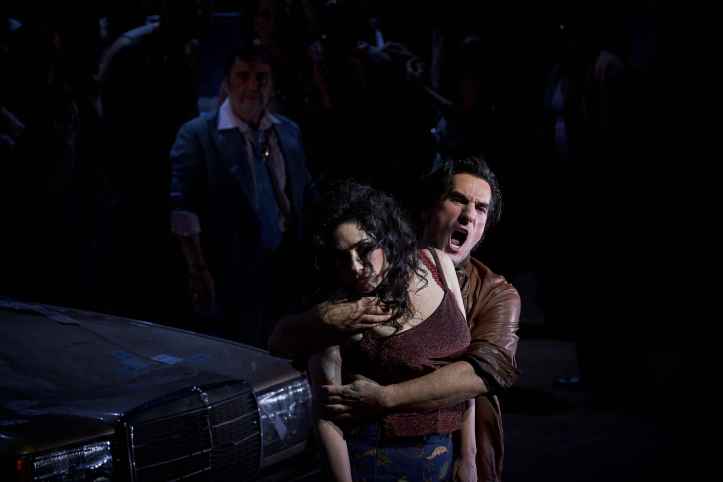

The year started with Jenůfa in Hamburg, with Eliška Weissová demonstrating some considerable volume as the Kostelnička. At the Liceu, Calixto Bieito’s now classic production of Carmen was revived with Rinat Shaham and Leonardo Capalbo. It might be over two decades old now, but it’s lost nothing of its searing power and psychological insight – and Shaham and Capalbo were riveting. I was also lucky to see René Jacobs conduct a period-instrument Carmen in Cologne. As always with Jacobs, it was revelatory. There wasn’t too much symphonic music this year, something I always say I’ll change. I did have the opportunity to visit the magnificent Sala São Paulo. What a stupendous hall that is! Converted from an old train station, the acoustic is easily the equal of the great concert halls of Europe and the house Orquestra Sinfónica do Estado de São Paulo is excellent. I also got to revisit the legendary Teatro Colón, sadly not for opera this time, but instead for a concert of symphonic music by Adams and Chin. The only new opera I saw this year was the premiere of Daan Janssens’ Brodeck at Opera Ballet Vlaanderen. Based on the novel by Philippe Claudel, it was a timely exploration of the impact of hate and prejudice. If the opera itself seemed to run out of steam in the second half, the performance was at the highest level imaginable and showed this ever-enterprising house at its considerable best.

In this Puccini year, his music was ever-present, starting with a Rondine at the Scala. Mariangela Sicilia was enchanting in the title role and Matteo Lippi ardent as Ruggero. Irina Brook’s staging was a bit cynical, although Riccardo Chailly and the Scala orchestra were predictably superb. Eleonora Buratto made her debut as Tosca in Munich. I was nervous that this glorious singer, surely the greatest Italian soprano before the public today, was taking on this iconic role too soon. I needn’t have worried. Both here and at the Santa Cecilia in October, she proved herself a tremendous exponent of this iconic role, bringing that unique sense of the union of text and line that Italians can bring. Also making his debut as Cavaradossi in Munich was Charles Castronovo, who sang his music with warm Italianate tone and immaculate control of dynamics. Ludovic Tézier was a thrilling vocal presence as Scarpia in Munich, although at the Santa Cecilia the impact of his singing was hampered by the acoustic. Castronovo also sang Pinkerton in Damiano Michieletto’s Madama Butterfly in Madrid, which he did with the utmost musicality and handsomeness of tone. Michieletto’s staging was revelatory. For once, Act 1 moved me more than it ever has before, bringing out the sheer horror of Butterfly’s impending fate. Even if Ailyn Pérez was vocally stretched in the title role here, the cumulative impact was immense. But perhaps the most impactful Puccini I heard this year was in his native Tuscany. In April, I had the privilege of seeing the great Zubin Mehta conducting Turandot at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, on the eve of his eighty-eighth birthday. Like so many, I learned the work though Mehta’s classic Decca recording and to hear him bring so much colour to the work, combined with that superlative chorus and orchestra was a real privilege. It was an experience I’ll never forget. Similarly, in December I saw a Gianni Schicchi that was so fully idiomatic, gloriously sung, with Roberto De Candia so healthy in the title role and Valentina Pernozzoli a fabulous Zita. To see this most Florentine of works, so well performed, in the city that has inspired so many artists over the centuries was simply a dream.

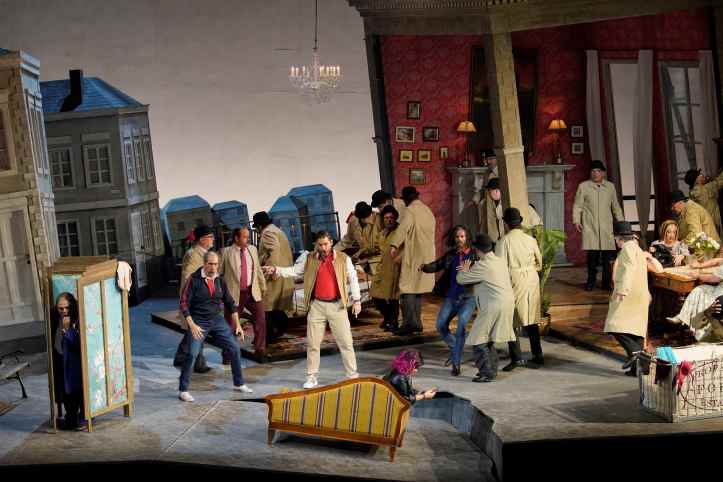

In December, I also got to see a Pagliacci at the Bologna Comunale. One might think it rather short measure for an evening’s entertainment, particularly given how hard it is to get to the Comunale’s temporary theatre from downtown. And yet, it was a thrilling evening, rendered more so by the sheer idiomatic verve with which the orchestra and chorus attacked their music. At the Donizetti Opera Festival in Bergamo, that festival once again confirmed its position as the place to go to hear the best, new bel canto talent. I was introduced to the enchanting soprano Giulia Mazzola as Norina in Don Pasquale, in a production that tried to add on a narrative layer that the work couldn’t sustain. In Roberto Devereux the following evening, Raffaella Lupinacci was a sublime Sara, while John Osborn gave us a singing lesson in the title role, and Jessica Pratt commanded the stage as Elisabetta. I also had the pleasure of visiting the beautiful Puglian town of Martina Franca for its annual festival. A Norma was hampered by some laborious conducting by Fabio Luisi and an incoherent staging by Nicola Raab, but it was saved by Airam Hernández’ stylish and immaculately-sung Pollione. The following evening, Ariodante was given by a youthful, mainly Italian cast, fabulously played under Federico Maria Sardelli, in a penetrating and cogent staging by Torsten Fischer. This was Händelian singing and playing at its very best.

In Helsinki, the Ring came to its big conclusion with a Götterdämmerung that reflected the course of the cycle: classic visuals, excellent singing, and superb orchestral playing. It was notable for Johanna Rusanen’s human and genuine Brünnhilde and Reeta Haavisto’s gleaming Gutrune. The choral singing in Act 2 was staggering in its amplitude. The Brussels Ring continues its course, although with an unexpected change of director following Romeo Castellucci’s departure from the project. In Walküre, Gábor Bretz gave us a Wotan sung like bel canto, bringing a welcome beauty of line to a punishing part, while Marie-Nicole Lemieux’s Fricka was magnetic. In Siegfried, Magnus Vigilius was tireless in his demanding assignment, while Pierre Audi’s staging was utilitarian. Common to both was Alain Altinoglu’s magnificent orchestra, the sheer quality of their outstanding playing confirming their place in the top 3 opera orchestras in the world currently, by my reckoning. The sheer personality and technical security of their playing was out of this world. In Cologne, I had the opportunity to hear a period-instrument Walküre under Kent Nagano’s direction. The instrumental sonorities were a revelation and Derek Welton was a vocally secure and indefatigable Wotan.

There was more German opera with a Tristan und Isolde in Palermo which was billed as Nina Stemme’s final account of the title role. One can only have gratitude for her service to this part over the years, although that night it was clear she was at the end of the road vocally with it. It now transpires that, that was not her final Isolde as she is due to sing concert performances in Philadelphie and Stockholm in 2025. Violeta Urmana gave us a glorious Brangäne that night and Michael Weinius was a brave and determined Tristan. Daniele Menghini’s staging gave us a lot to look at. But it was Omer Meir Wellber and his stupendous orchestra that will stay with me from that evening. Their playing, full of lyrical longing, pulsating force, and throbbing urgency made this score sound thrilling. There were also three, Elektras. In Baden-Baden, Stemme gave a determined performance in the title role with the luxury of the Berliner Philharmoniker on remarkable form in the pit. In Cologne, Allison Oakes gave us an honest account of the title role, while Felix Bender’s conducting was some of the best I’ve heard in this score. In Naples, the evening was hampered by Mark Elder’s pedestrian conducting (1 hour and 50 minutes with cuts!), but it marked a momentous occasion: Evelyn Herlitzius, the greatest Elektra of our time, making her debut as Klytämnestra. It was an emotional evening, watching the torch being passed to Ricarda Merbeth and a reminder that time doesn’t stand still. Yet, for the rest of my life, Herlitzius’ Elektra will stay with me as one of the greatest assumptions of any role I have had the privilege of seeing. And now, hopefully we have many more Klytämnestras to look forward to from her. As hopefully we do of her Herodias, which Herlitzius debuted in Dresden in November, notably in the theatre where Salome was premiered. The playing of the Staatskapelle was unimpeachable, full of colour. On the other side of the Alps, I visited the Teatro Verdi in Trieste for the first time to see Ariadne auf Naxos. The house orchestra made that score soar in the most wonderful way.

Other than the Bolognese Don Giovanni, there was no other Mozart in my operagoing this year. Something I hope to rectify next year. I did get to see an Iphigénie en Tauride in Flanders. In Reinoud Van Mechelen and Kartal Karagedik we had a duo of Pylade and Oreste that would be hard to be bettered. Michèle Losier is a singer I have a huge amount of affection and appreciation for, although here her Iphigénie was sung with genuine feeling but was verbally indistinct, a real surprise for a singer who has given me so much pleasure in the French repertoire. In Lisbon, I saw the São Carlos forces in a revival of Georges Delnon’s Fidelio, which convinced me so much more than it did when I had seen it in Bologna five years previously. At the Scala I saw Damiano Michieletto’s staging of Médée, which brought his considerable psychological insight to this most iconic of diva vehicles.

2024 might have been the Puccini centennial, but it was Verdi who was most prominent in my operagoing this year. The year ended with a Forza del destino at the Scala, notable for the magnificent playing of the Scala orchestra and Riccardo Chailly’s invigorating conducting that filled the work with drama. Luciano Ganci and Ludovic Tézier were both superb as Alvaro and Carlo respectively, while Anna Netrebko’s Leonora was burdened with intonation issues and lack of radiance in her singing. The São Carlos gave us an uplifting Falstaff with Pietro Spagnoli giving us a terrifically witty account of the title role. In València, I saw a Ballo in maschera in a staging by Rafael R Villalobos that looked great, but betrayed rather rudimentary direction of the singers. As always there, the house orchestra and chorus were outstanding. In Turin, Riccardo Muti brought a lifetime of experience to his conducting of Ballo. His Renato was Luca Micheletti who gave us an electrifying account of his ‘eri tu’, singing with the kind of textual and musical understanding that cannot be taught. A thrilling artist. A Nabucco in Cologne was notable for Sesto Quatrini’s vigorous conducting, although it was disappointing he did not encourage his singers to ornament their lines. Marta Torbidoni was a fearless Abigaille. Like many people I’m sure, I learned Simon Boccanegra from Claudio Abbado’s classic recording made at the Scala, with Piero Cappuccilli, Mirella Freni and Josep Carreras. So, it was a genuine treat to be able to return to that legendary house this year, to see a cast that would likely be today’s equivalent of that classic lineup. Luca Salsi was world-weary in the title role, Eleonora Buratto was simply exquisite as Amelia, while Charles Castronovo gave us a gloriously ardent Adorno. In a neat concidence, it was Claudio’s son Daniele Abbado who provided the stage direction. I saw another Boccanegra, this time in Rome, also featuring Buratto’s heavenly Amelia, who in her limpid beauty of tone, idiomatic use of text and impeccable line manifested the best of Italian singing. Proof indeed that there is some fabulous Verdi singing out there today.

As every year, I would like to pull out three very personal choices of the shows that gave me particular pleasure this year, alongside one turkey. This year, the choice of the best of 2024 has been incredibly difficult. So much of what I saw could easily have been considered the best. The Florentine Gianni Schicchi or Martina Franca Ariodante would probably have made it in another year. That said, the choice of turkey of 2024 was easy: Melly Still’s staging of Die Schöpfung in Cologne. Musically it was more than decent. Yes, Marc Minkowski’s tempi were bit too slow for my taste, but his phrasing was stylish. The youthful cast gave a good account of themselves, with some very pleasing singing. And yet Still’s staging was a perfect example of just because something’s possible, it doesn’t mean it has to be done. It was barely coherent, with a closing tableau that seemed to point to the evils of capitalism, yet hadn’t explored that theme throughout the evening, and required a troupe of danseurs and danseuses to randomly gyrate around the stage. It felt like the kind of thing a Cambridgeshire Sunday school teacher might come up with. Not that I’ve had the experience of attending a performance at a Cambridgeshire Sunday school, but Still’s staging was what I imagine it would be like.

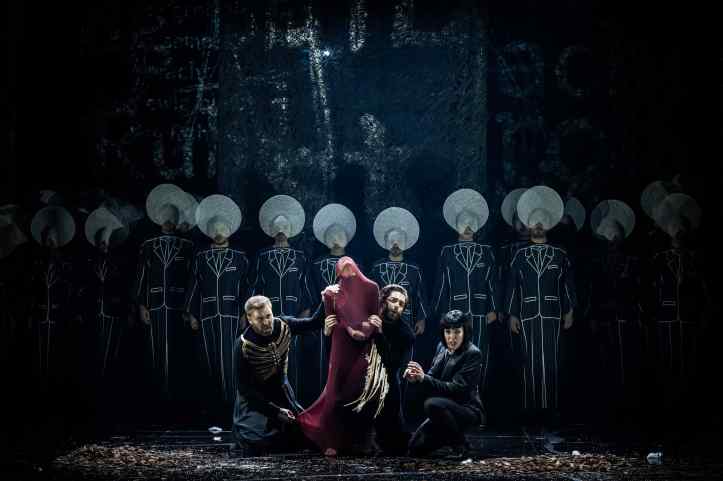

There are some evenings in the theatre that feel like they change something in you. In the cold light of day, I don’t know what that something was. Yet after David Bösch’s staging of Die Frau ohne Schatten in Dresden, it felt that nothing would be the same again. Bösch managed to give us a real ‘show’, that was visually a feast for the eyes, while he also managed to humanize what can be an impenetrable story, making it full of real, flesh and blood characters. The score was played with such marvellous fulness and depth by the Staatskapelle, while Christian Thielemann navigated his forces through the fragrant score with great assurance. Vocally, it was tremendous. Camilla Nylund sang the Kaiserin with seemingly effortless ease, as did Eric Cutler as the Kaiser. Miina-Liisa Värelä was a deliciously game stage presence and sang her music in her juicy soprano, while Oleksandr Pushniak was a moving and deeply human Barak. The cast was capped with the great Evelyn Herlitzius as the Amme, giving another definitive assumption of a Strauss role, both in her electric stage presence, clarity of diction and sheer thrilling amplitude.

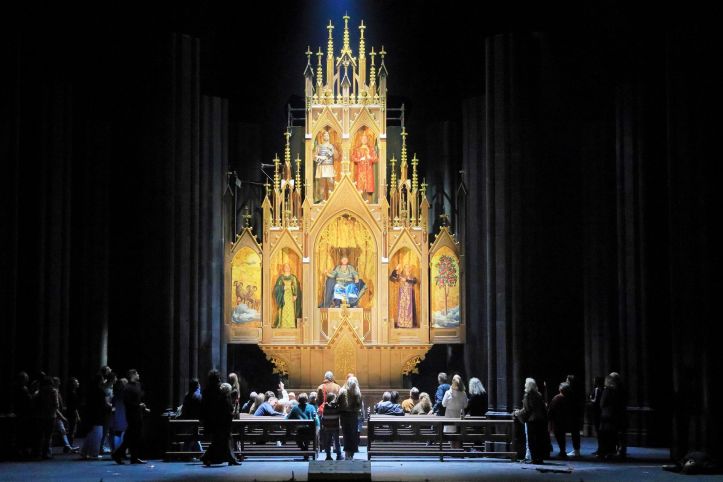

In a year that has seen so many houses undertake Wagner’s Ring, it’s perhaps unsurprising that two separate Rings have found their way into the next two slots. In Munich, Tobias Kratzer undertook the start of his journey, which will resume in a couple of years’ time. His Rheingold was superb. It genuinely felt that one was witnessing a Ring for the second decade of the twenty-first century, both in the technological audacity of his stagecraft and the sense of a unified creative team at the peak of its powers. There was also a sense of that rot at the heart of elite power, sustained by a populace desperate for easy answers that characterizes our uncertain times. In his staging, he holds up a mirror to today and challenges us to reflect. Musically, Vladimir Jurowski led a Staatsorchester on thrilling form: this is of course a piece that saw its first performance in that very theatre. The casting also reflected a generational change, with some younger Wagnerian talents brought to the fore, not least in Nicholas Brownlee’s securely sung Wotan, or Sean Panikkar’s verbally incisive Loge. There wasn’t a weak link in the entire cast.

Then there was the start of the Bologna Ring. The Comunale is one of the most Wagnerian of Italian theatres and while this Ring is being performed only in concert form, the orchestra is so far giving us all the drama we need. Under the musical direction of Oksana Lyniv, the band brought out a sheer rainbow of colour in Rheingold, even if the brass playing was a bit accident-prone. Yet it was in Walküre that the Bologna Ring stepped up not one but several gears. That night felt like one of those evenings in the theatre where everyone just brought it. Stuart Skelton might have his vocally best years behind him, but he managed to get through Siegmund with his dignity intact and sang it with honesty. Thomas Johannes Mayer may also vocally not be in the first flush of youth, but he used his experience to give his Wotan even more depth and emotion. Sonja Šarić gave us a radiant Sieglinde, and Ewa Vesin a thrilling Brünnhilde showing the difference a real bel canto technique can make in this music – the sheer amplitude of her war cries was exhilarating. The orchestra was on superlative form for their chief, Lyniv. They played his score like it was real music, pulling out a sense of line that just enhanced the emotion within. This score has never moved me as much as it did that night, because the orchestra made it ‘sing’ as much as the principals did. I simply can’t wait for the next two instalments in the spring and fall of 2025 respectively.

And there you have it, that was the musical year in review. In retrospect it’s been a pretty good one, with so many highlights, so many memories of fantastic performances, and the pleasure of visiting great venues. It’s been a delight having you along for the ride. All that remains for me is to wish you all the very best for 2025, with many happy operatic adventures to come. Bonne année!