Saariaho – Innocence

Waitress – Hanna Dóra Sturludóttir

Mother-in-Law – Katherine Allen

Father-in-Law – Tuomas Pursio

Bride – Margot Genet

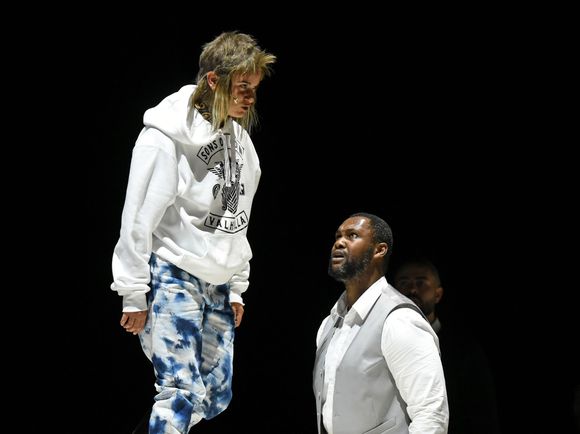

Groom – Khanyiso Gwenxane

Priest – Philipp Kranjc

Teacher – Anke Sieloff

Student 1 (Marketa) – Erika Hammarberg

Student 2 (Lilly) – Bele Kumberger

Student 3 (Iris) – Elisa Marcelle Berrod

Student 4 (Anton) – Sebastian Schiller

Student 5 (Jerónimo) – Pablo Antonio Alvarado Mejía

Student 6 (Alexia) – Danai Simantiri

Chorwerk Ruhr, Neue Philharmonie Westfalen / Valtteri Rauhalammi.

Stage director – Elisabeth Stöppler.

Musiktheater im Revier, Gelsenkirchen, Germany. Saturday, January 11th, 2025.

Since its world premiere at the 2021 Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, the late Kaija Saariaho’s final opera, Innocence, has led a peripatetic existence in Simon Stone’s original staging. I was fortunate enough to see that premiere run in Aix and, at the time, it very much felt that we were witnessing a true twenty-first century masterpiece. For its German premiere, the enterprising Musiktheater im Revier in Gelsenkirchen has chosen to produce the work in a new staging by Elisabeth Stöppler, with a brand-new cast – although the originally-scheduled Benedict Nelson (photographed) as the Father-in-Law was replaced tonight by Tuomas Pursio. It also meant that the extraordinary Vilma Jää, who has incarnated Marketa in all of the productions to date around the world, was here replaced by Finnish folk singer Erika Hammarberg.

The fact that Innocence is already receiving a new production with a new cast only four years after its world premiere, is a sign of confidence that Saariaho’s opera has a bright future as a repertoire work. I was once again struck by the sheer vividness of her soundworld and the incredibly moving drama of Sofi Oksonen and Aleksi Barrière’s libretto. Indeed, seeing it for a second time made it even more painful to watch, simply because one was even more keenly aware of the tragedy about to unfold.

Stöppler’s staging unfolds on a two-storey set, by Ines Nadler. Initially we saw the wedding party take place on the upper level, while the school students circulated on the lower level. As the evening progressed, the characters started to change place, their memories and fates taking them physically to the different places that their psyches took them to. More than in Stone’s staging, it felt that Stöppler questioned even more explicitly what ‘innocence’ truly means. I felt a sense throughout the evening that nobody on that stage was truly innocent – whether the father-in-law who taught his son how to shoot, or the fellow student, Iris, who had also planned the school shooting along with the perpetrator. This reconfirmed in my mind the sheer strength and vividness of Oksonen and Barrière’s libretto, in how they take us on that journey deep into the minds of the victims and the nature of the guilt that they live with.

Another aspect that I felt Stöppler brought out even more strongly that Stone was that of the class relations between Tereza and the Mother-in-Law. The latter, dressed in her wedding finery enjoying a glass (or six) of champagne that Tereza, dressed all in black, served her. There was a sense of entitlement and superiority to the Mother-in-Law here, that contrasted so strikingly with Tereza’s pain and grief, particularly in how she so eagerly wanted to call her recently-released, perpetrator son to invite him to the wedding. Stöppler had the chorus sing at the back of the stage, seated singing from music stands. This helped acoustically, making the choral sound more prominent in the textures compared to Aix, but also served dramatically to give us a sense of helpless witnesses watching and commenting on a tragedy that they could do nothing to stop. There were a few moments that didn’t quite convince – having a group of young people extras running around at the back of the stage was slightly distracting, and Tereza’s silent screaming towards the start was also a bit de trop. Yet the way that Stöppler had the set move back as the evening progressed, the word ‘innocence’ initially lit up and then going dark, was immensely affecting.

This was my first visit to this handsome venue and I was immediately struck by the confidence and clarity of the playing of the Neue Philharmonie Westfalen. They played this complex and multi-fragranced score with total command and assurance, under the clear direction of Valtteri Rauhalammi. He brought out both the lyricism and violence inherent in the score, opening the evening with a soulful and haunting bassoon melody. The complex textures, with pounding, insistent rhythms and aching string glissandos taking us deep into the characters’ psyches were confidently brought out. To play such a complex score with such complete and total assurance was a major achievement. Similarly, the singing of the Chorwerk Ruhr was superb in its discipline, blend and tuning. Prepared by Sebastian Breuing, the luminous sound that they produced, with clarity and focus of tone, was seriously impressive.

The individual singing was always honest and filled with feeling. Hanna Dóra Sturludóttir sang Tereza in a ripe mezzo with impeccable English diction. She wasn’t afraid to compromise the beauty of the tone to portray Tereza’s pain and despair, bringing us into deep into her world. Katharine Allen dispatched the Mother-in-Law’s music in an attractive lyric soprano, with a refreshing fast vibrato, ably coping with the higher-lying writing. Her diction was, however, rather foggy, requiring me to resort to the German surtitles, even though her character sang in both of my mother tongues. Pursio, familiar from the world premiere run, sang the Father-in-Law in a warm, rich baritone, with great authority. To see the disintegration of his character from upright father to a broken shell of a man was heartbreaking.

Margot Genet also sang the Bride’s music in a rich, rounded soprano that negotiated the registers with ease. Khanyiso Gwenxane sang the Groom in a plangent tenor, his passionate entreaties for forgiveness, when it became clear that he was also part of the shooting plot, were deeply affecting. As the Priest, Philipp Kranjc sang in a firm, slightly grainy bass, a tower of strength and humanity. Hammarberg had a tall order in taking over the role of Marketa after Jää’s extraordinary assumption. She was supported by the sound designers who gave her voice additional reverberation, reinforcing the other-worldly effect of her singing. The voice has a crystalline purity that allowed her to produce haunting melismas at the top of the voice, reminding us of a lonely bird in flight.

The remaining roles were taken, as at Aix, by actors from outside of the operatic tradition. Pablo Antonio Alvarado Mejía’s delivery of his lines was deeply affecting, finding a pain that struck deep. Sebastian Schiller was unflinching, constantly moving on stage, unable to sit still, while Bele Kumberger moved between speech and song, the words always forward. As the Teacher, Anke Sieloff, intoned her lines in sprechgesang with precision and in impeccable English, while Danai Simantiri was an eloquent stage presence. I found it interesting how Stöppler had Elisa Marcelle Berrod’s Iris initially stalk the stage, making us think she was the perpetrator, bringing an ambiguity to her stage presence that was deeply disturbing. That said, I did find Berrod’s delivery of her lines to lack ideal clarity of diction – perhaps it was the amplification, but her lines lost impact due to the lack of clarity.

This was an evening that showed this enterprising theatre at its very best. That this work could be given such a confident and enthralling performance at the highest level is testament to its stature as one of the great operas of the twenty-first century. Stöppler’s staging was thrilling and disturbing in equal measure, indeed I found it much more complex and nuanced than Stone’s. The audience responded at the close with an extremely warm ovation. There are a handful of performances left, if you can get to Gelsenkirchen, it’s most definitely worth the journey.

Thank you so much for this.

[…] opera that has clearly become a repertoire piece in just four years is the late Kaija Saariaho’s Innocence. I saw its German premiere production in Gelsenkirchen, in a staging by Elisabeth Stöppler. The […]