Verdi – Un ballo in Maschera

Amelia – Laura Stella

Riccardo – Matteo Lippi

Ulrica – Chiara Mogini

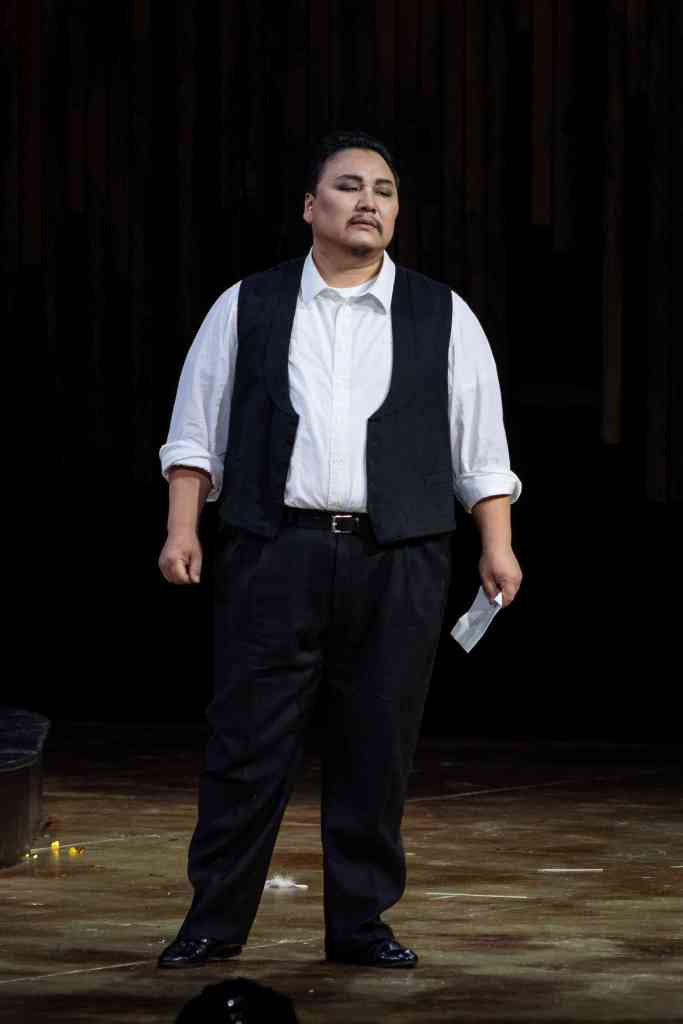

Renato – Amartuvshin Enkhbat

Oscar – Claudia Ceraulo

Silvano – Andrea Borghini

Samuel – Zhang Zhibin

Tom – Park Kwangisk

Un giudice – Cristobal Campos Marin

Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna / Riccardo Frizza.

Stage director – Daniele Menghini.

Teatro Comunale di Bologna – Comunale Nouveau, Bologna, Italy. Tuesday, April 15th, 2025.

This new production of Un ballo in maschera opened at the Teatro Comunale di Bologna’s temporary home on Sunday. As is usually the case here, the run was double-cast, although there was a further change this evening with Laura Stella jumping in for an indisposed Maria Teresa Leva. The staging was confided to Daniele Menghini. I must admit to some significant trepidation when I saw his name listed as the stage director. My previous encounters with his work have been less than satisfactory. These consisted of a Carmen in Macerata that made this vibrant opera tedious, a Tristan in Palermo that had a naked man perambulating the stage, and an Elisir in Turin that sucked the life out of that glorious opera.

I’m very happy to report that on this occasion, that trepidation was misplaced. Unlike his other productions, Menghini instead here focuses on actually telling the story, rather than adding extraneous layers of visual ‘noise’ that drown out the work. He sets the action in a simple tiered set, by Davide Signorini, which is accessorized for each scene with various bits of stage decoration. The set is dominated by a throne to the left, through which a strange, crawling danseur exits in the Ulrica scene, and is later covered in skulls in the closing scene. It struck me that Menghini might be making a statement about colonialism here – the fact that America was built on the skulls of its aboriginal people.

Similarly, throughout the evening, Menghini makes use of some striking stage pictures. The skeleton at the back of the stage during the Renato/Amelia confrontation, suggesting a brutality that was all-encompassing in this conspiratorial society. Having Riccardo sing his big ‘Ma se m’è forza perderti’ in front of the curtain, meant that it could open to show a vibrant ball scene with a full stage. So vibrant in fact, that the lady in front of me couldn’t help but take a photo. The sight of Amelia in the horrid field, surrounded by skulls, was also particularly striking. I do have reservations about some of Menghini’s personenregie. Amartuvshin Enkhbat as Renato is a bit of a statuesque actor, and he appeared to have been left to his own devices. On the whole, however, this is the most successful staging I’ve seen by Menghini, simply because he concentrates on the clarity of his storytelling and proved himself willing to trust the work.

Riccardo Frizza led a Comunale orchestra on luminous form – even in this difficult acoustic. He found a mahogany depth to the string tone, encouraging his players to experiment with vibrato, pulling the vibrations from the sound to make the Ulrica scene even more creepy. The wind playing also had a captivating, cantabile beauty. I did, however, find Frizza’s tempi surprisingly sluggish. The closing anthem of Act 1 seemed far too ponderous in approach, while ‘morrò’ seemed to just grind to a halt. I found attack to be a bit soft-grained, and throughout I longed for Frizza to bring that lightness of approach and sheer dynamism that he brings to his Donizetti. It was an engaging enough reading, he kept the disparate forces appropriately together, but I missed the vitality and vigour I’ve heard him bring on other occasions. The chorus, prepared by Gea Garatti Ansini, confirmed their place as the finest opera chorus in the Italian Republic currently. The tenors and basses sang with supreme precision of tuning in the unaccompanied off-stage section at the end of Act 2, with the basses warmly resonant. The sopranos and mezzos sang with warm tone and agreeable blend.

Matteo Lippi gave us a wonderful Riccardo. What a delight it was to hear able to fully rise to this music, singing with eloquent diction and warm, sunny tone – not to mention an impeccable legato. Furthermore, he had room to spare in the final scene, the voice seemingly unlimited in stamina, despite the relatively demanding assignment, never forcing the voice further than it can go. The voice has such brightness and warmth to the tone, such agreeable sunniness, that his singing gave an immense amount of pleasure. Amartuvshin sang with impressive stylistic awareness and clarity of diction. The tone itself is quite complex in texture, warm and rich. He’s also the owner of an appropriately smooth legato, without a trace of aspiration. He brought a genuine sense of feeling to the middle section of his ‘eri tu’, where so many before have just blasted it out. Here, Amartuvshin found a beauty and contemplation that very much brought his character to life. If only he had been given some stronger stage direction by Menghin. Make no mistake, this gentleman can certainly sing.

I don’t know when Stella received the notification that she would be going on as Amelia. Perhaps some last-minute nerves might explain the fact that it took a couple of acts for her intonation to settle. Her big scene at the horrid field saw her get through the ascent to the high C through sheer willpower, the voice with a metallic core but perhaps lacking in spin. Once she got to ‘morrò’ something happened. Stella pulled back on the tone and used the dynamics to bring Amelia’s pain to life, sustaining the extremely long lines, particularly at Frizza’s incredibly slow tempo, with ease and feeling. No doubt that with more time and notice, Stella would give us an even more deeply-felt Amelia.

The remainder of the cast reflected the excellent standards of the house. Chiara Mogini was a confident Ulrica. She was unafraid to go for the chestiness, while she was utterly fearless on top, bringing out the hieratic declamations of the sibyl to life with forthright generosity. Claudia Ceraulo was a crystalline Oscar, turning the corners with ease and panache, with a more than creditable stab at a trill. Both Zhang Zhibin and Park Kwangisk, as Samuel and Tom respectively, sang with warm resonance, while Andrea Borghini sang Silvano in a handsome baritone, one I’d like to hear more of.

This was undoubtedly an engaging evening in the theatre. Menghini’s staging is by far the most successful thing I’ve seen from him, simply because he focuses on the clarity of the storytelling and creates effective stage pictures, in collaboration with his creative team. Frizza’s reading felt quite sluggish on the whole, but he did obtain some superb playing from the Comunale orchestra, again cementing their place as one of the finest orchestras in the Italian Republic. The singing had much to enjoy, with Lippi’s Riccardo singing with such Italianate warmth and generosity. The audience responded at the close with generous ovations for the entire cast.

[…] to ornament the lines. In Bologna, Daniele Menghini redeemed himself with a cogent staging of Un ballo in maschera, with the Comunale chorus and orchestra on magnificent form. In Monte-Carlo, Zanetti led a […]