Thomas – Hamlet

Hamlet – John Osborn

Ophélie – Sara Blanch

Gertrude – Clémentine Margaine

Claudius – Riccardo Zanellato

Laërte – Julien Henric

Le spectre du roi – Alastair Miles

Marcellus – Alexander Marev

Horatio – Tomislav Lavoie

Polonius – Nicolò Donini

Premier fossoyeur – Janusz Nosek

Deuxième fossoyeur – Maciej Kwaśnikowski

Coro Teatro Regio Torino, Orchestra Teatro Regio Torino / Jérémie Rhorer.

Stage director – Jacopo Spirei.

Teatro Regio Torino, Turin, Italy. Tuesday, May 27th, 2025.

This new production of Hamlet at the Teatro Regio Torino, is the first to have adopted the new critical edition by Hugh Macdonald and Sarah Plummer, published by Bärenreiter. The main difference in this new edition is that it returns to Thomas’ original intentions, with the title role performed by a tenor, rather than the baritone we are used to hearing. Even though Thomas had conceived for the title role to be sung by a tenor, there was no suitable artist available at the Opéra at the time, which meant he subsequently revised the role for baritone and this is the version that has been performed up until now. The main difference between the two is a matter of the brilliance of the sound, particularly with a tenor with the kind of bright timbre that John Osborn has, whereas the baritone version sounds introspective in a way, arguably more appropriate for the tortured nature of the title role.

Jacopo Spirei’s staging seems to set the work around the time of composition. The palatial set is certainly grand to look at, with the big festive scenes populated with the large chorus inspired to strike poses of general merriment, including sideways swaying to add that festive air. It’s certainly an expansive show to look at, although I must admit to some sympathy for Clémentine Margaine’s Gertrude who, for much of the evening, had to occupy the stage with the most unfortunate ginger beehive wig – costumes by Giada Masi. Hamlet’s grasp of sanity was tenuous from the start, with John Osborn jumping around the stage in an uncontrolled fashion during his first confrontation with Claudius and Gertude.

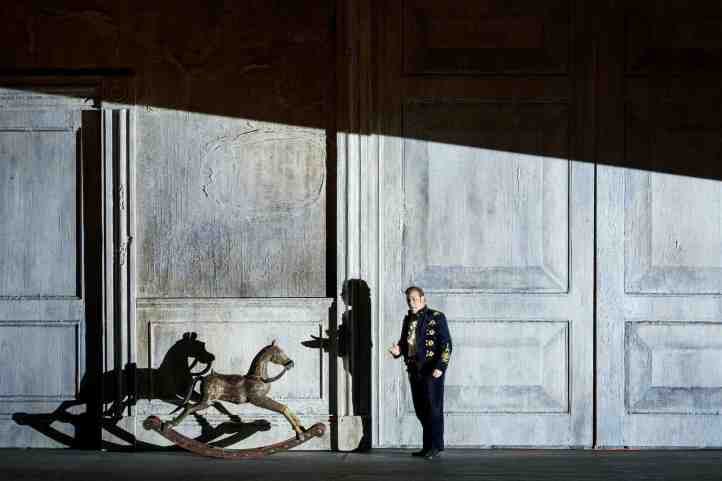

Spirei clearly makes a connection between Hamlet’s childhood and the action taking place. When the ghost appears, he does so as a suited figure who sings from fields of wheat at sunset, or tends to a young child in the same outfit as Hamlet. Yet what the nature of that connection is, and why Spirei felt it necessary to include it, is one I’m not convinced he fully explores. Yes, Hamlet sings his final scene on the wooden horse his father gave him in one of his ghostly apparitions, but the why is something that isn’t fully explored. Moreover, Spirei has a group of a dozen extras, listed in the program book as ‘performers’, who are constantly present on-stage reading books, or walking around with the books on their heads. At first, I did wonder if Spirei was using them to represent the characters in Shakespeare’s play who don’t appear in the opera, but instead their presence felt distracting for the most part. That said, during the scène de la folie, the ‘performers’ did add an interesting visual touch. The women were dressed in white dresses, as was Ophélie, while they waved books around to imitate birds in flight. Later in the scene they wrapped Ophélie in a white shroud in which she perambulated the stage – it was undoubtedly a haunting image. For the most part Spirei’s staging looks good and managed to tell the story with relative clarity. And while there were some moments of visual clutter that distracted rather than enhanced the narrative, on the whole it was an effective enough piece of theatrical storytelling.

It’s hard to imagine a conductor better appointed to lead this opera than Jérémie Rhorer, and he most certainly did not disappoint tonight. He understands profoundly how this music should go and the hours sped by. He and Spirei had made the decision to cut the Act 4 ballet. While it is one of the weakest moments of the score, it would have certainly been good to have had the opportunity to hear it. Rhorer led the score with captivating vigour, rhythms springy and nicely pointed, while underscoring long, cantabile lines. He encouraged his wind players to phrase with beauty and generosity, including the haunting saxophone solo. The Regio orchestra responded with superb playing for him, although there were a few passing passages of sour string intonation. What tonight reminded us of, was Rhorer’s impeccable ear for orchestral sonorities. So much in his interpretation reminded us that Thomas was a figure who both echoed the past, but also looked forward to the future in his orchestral writing. The Regio chorus, prepared by Ulisse Trabacchin, was on tremendous form. Spirei knows that to allow the audience to bathe themselves in the choral sound, they need to be placed at the front of the stage at times. The noise the chorus made was huge, filling the auditorium in an ecstatic wave of sound in the opening celebration scene, the combination of the chorus and whooping trumpets just thrilling to hear. The choral sound had excellent blend, with the sopranos singing with impressive evenness of tone. It was a big night for them and they more than rose to the occasion.

Diction throughout the cast was impeccably clear – although the chorus could have sharpened up their pronunciation of those nasal diphthongs. For this production, the Regio offered Italian surtitles together with the French original, although, given how clear the text was, there was no need to refer to them. Osborn is, of course, highly experienced in the French repertoire, and his assumption of this complex role reflected that long understanding of the style. Having a tenor sing the role, meant that there was a sense of heroism in Hamlet’s promises of revenge that felt extrovert and focused, although Osborn pulled back on the tone with delicacy in his big ‘être ou ne pas être’ soliloquy. The voice is bright and forwardly produced, the top focused and able to rocket into the house with exciting openness. Osborn’s tenor sounds so utterly healthy and able to do whatever he asked of it. Undoubtedly an exciting addition to his repertoire.

Sara Blanch sang Ophélie with genuine delicacy. She’s a very physical stage presence, able to dispatch immaculate coloratura while dancing around the stage. Blanch blended magically with Osborn in their Act 2 duet, both voices rising with ease through the registers, although I’m not convinced that Spirei having them copulating while rolling around on the floor added much. Her scène de la folie was utterly gripping, the voice able to respond with staggering facility to anything asked of it, those huge leaps dispatched as it they were the easiest thing in the world, and the ascent to the treacherous high E made to sound genuinely insane. Another gripping account from this intelligent singer, sung in excellent French.

Margaine swept all before her as a commanding Gertrude. The voice has thrilling amplitude, filling the house with waves of sound. Margaine’s mezzo is utterly healthy, able to cross the registers without a hint of a break, always absolutely even from top to bottom. Naturally, it goes without saying that so much was sung off the text, the words always clear and filled with meaning. She was magnificent. It sounded to my ears that Riccardo Zanellato’s Polonius took a while to find his best form, the voice initially rather grainy, though lugubrious. Later, he found a Verdian depth to his scene with Nicolò Donini’s confident Polonius, offering a tortured reading of the guilty king.

Julien Henric brought an easy top to his singing of Laërte, the high-lying lines holding no terrors for him. Alexander Marev sang Marcellus in a narrow, robust tenor, while Tomislav Lavoie sang Horatio in a firm, healthy baritone. The passage of the years might be audible in Alastair Miles’ bass, the tone not quite as generous of yore, but his stage presence and verbal acuity are undimmed. We also had a very impressive duo of gravediggers from the Regio’s ensemble in Janusz Nosek and Maciej Kwaśnikowski, two healthy and youthful voices with impressive sheen.

This was a fascinating opportunity to hear Thomas’ original thoughts on his Hamlet, a version that makes the title role seem more heroic and less tortured than the baritone version. One could hardly image a better cast than the one the Regio assembled for us, particularly in Osborn, Blanch and Margaine. Spirei’s staging had its positive aspects, even if the presence of the extras felt more distracting than insightful. Rhorer’s conducting was marvellous, bringing the score to life in a way that made the hours pass by like seconds. The audience responded at the close with an enormous ovation for the entire cast.

[…] Violeta Urmana descending from the flies on a silver throne. In Turin, we got to hear Thomas’ Hamlet in its original version for tenor, very different to the customary baritone version. One could […]