Lehár – Die lustige Witwe.

Baron Mirko Zeta – Alberto Petricca

Valencienne – Cristin Arsenova

Graf Danilo Danilowitsch – Alessandro Scotto di Luzio

Hanna Glawari – Mihaela Marcu

Camille de Rosillon – Valerio Borgioni

Vicomte Cascada – Cristiano Olivieri

Raoul de Saint-Brioche – Francesco Pittari

Bogdanowitsch – Giacomo Medici

Sylviane – Laura Esposito

Kromow – Stefano Consolini

Olga – Federica Sardella

Pritschitsch – Davide Pelissero

Praškowia – Elena Serra

Njegus – Marco Simeoli

Lolo – Camilla Pomilio

Dodo – Giulia Gabrielli

Jou-Jou – Silvia Giannetti

Frou-Frou – Lucia Spreca

Clo-Clo – Sara Bacchiocchi

Margot – Roberta Minnucci

Coro Lirico Marchigiano “Vincenzo Bellini”, FORM – Orchestra Filarmonica Marchigiana / Marco Alibrando.

Stage director – Arnaud Bernard.

Macerata Opera Festival, Sferisterio, Macerata, Italy. Sunday, July 27th, 2025.

Tonight’s performance of Die lustige Witwe should have been my second evening at this year’s sixty-first edition of the Macerata Opera Festival. Unfortunately, last night’s Macbeth was initially delayed by rain, then cancelled outright two-and-a-half hours after curtain time due to an issue with the lighting effects. Having kept the public and musicians in the venue, it’s disappointing that we didn’t get at least the performance with the lights on, particularly given the cast was an interesting one. Fortunately, this evening’s performance of Lehár’s masterpiece went by almost without a hitch, a very brief pause due to some light rain ten minutes before the end, the only meteorological interruption.

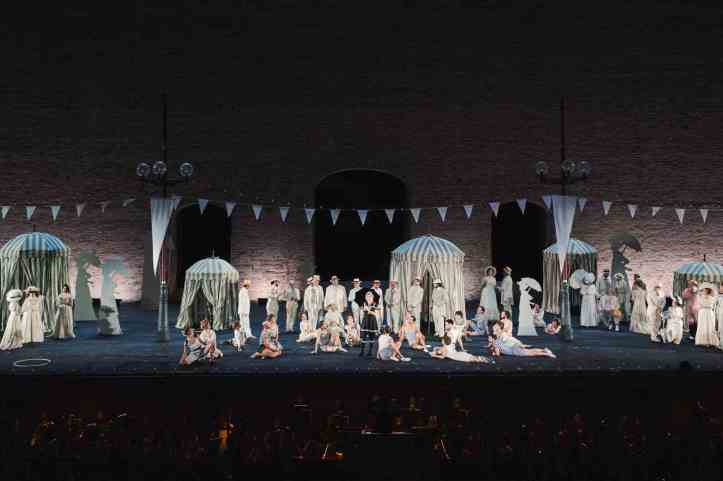

The festival chose to perform the work in Gianni Santucci’s Italian translation, who also served as the choreographer for the evening. I must admit that it worked especially well; the translation was musical and logical, while also being full of humour and affection. The stage direction was confided to Arnaud Bernard. The Sferisterio, an outdoor arena, is a difficult theatrical space to manage, with a wide yet shallow stage. Bernard, together with Santucci, managed it superbly. He centred the actions of the principals in the central third of the stage, while the two outer thirds were occupied by choristers milling around, yet never distracting from the focus on the principals. The arena itself is also particularly wide and, since my seat was right in the middle, I cannot comment on sightlines at the extremities of the venue, though my impression was that by focusing the key actions in the centre of the stage, Bernard ensured that they were visible to all.

The costumes, by Maria Carla Ricotti, were lavish and reflected late nineteenth-century Paris, France, placing the action in the time of the libretto. The sets, by Riccardo Massironi, were simple but effective: some banquettes scattered around the stage in Act 1, tents to reflect the coast (and the pavilion, here a ‘chiosco’) in Act 2, and statues of grisettes in Act 3. Bernard, together with conductor Marco Alibrando, wasn’t afraid to add additional music, opening the evening with a funereal procession for Mr Glawari to the strains of Chopin’s ‘Marche funèbre’. Act 3, saw Danilo and Hanna’s realization of their love accompanied by the opening measures of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, while they also included a riotous account of the cancan from Orphée aux enfers earlier in the third act. Indeed, that opening procession which saw Hanna shed her widow’s robes and reveal herself in full glamour just at the moment Lehár’s music started, seemed to set in train an uplifting evening that just grabbed the audience and didn’t let go. Even with the long passages of dialogue, the evening felt ideally paced, never dipping in tension. The sheer colour and abandon of the ballet, who also threw Cristin Arsenova’s Valencienne into a somersault, was tremendous. Yet, Bernard also managed to explore the melancholy there in the score, that feeling that there is such a thing in life as a second chance, through the subtlety and intricacy of his personenregie. This was escapism at its best, and the audience responded frequently with laughs and applause.

Even in a difficult open-air acoustic, Alibrando managed to conjure up a seemingly unlimited palette of tone colours from the musicians of the FORM – Orchestra Filarmonica Marchigiana. The folksy colours of the Pontevedran dance at the start of Act 2 were fully brought out, while the perfumed atmosphere as Camille and Valencienne sang of the pavilion was ravishing in its beauty. To achieve this wealth of sound in a bone-dry acoustic such as this is really quite extraordinary. Alibrando was also alive to the constant dance presence in the score, giving us lilting movements that seemed to constantly sweep us along almost imperceptibly. There was a lyricism to the playing that gave a great deal of pleasure, particularly in how the solo cello phrased those soaring lines with cantabile beauty.

In the title role, Mihaela Marcu was a delightfully engaging presence. She confidently dispatched her dialogue, holding the stage with elegance and generosity. I found Marcu’s singing to have many positive aspects. Her breath control in a ‘Vilja-Lied’ taken at a very slow tempo was seriously impressive, as was her sustained piano at the top of the voice. However, Marcu also had a tendency to dwell on the southern side of the note and, when she put pressure on the tone, it vibrated with wide generosity. There was so much I enjoyed in her singing and she clearly has much to offer, yet the intonation issues and wide vibrato were distractions. Marcu also took the end of ‘Lippen schweigen’ up the octave with Alessandro Scotto di Luzio’s Danilo, which was an unfortunate choice. I found Scotto di Luzio’s Danilo to be interesting. A light, lyric tenor, looking at his repertoire, he shares many roles in common with Valerio Borgioni who sang Camille. The two singers, could not be more different, however, in that Scotto di Luzio’s voice is darker in colour, perhaps also due to the lower tessitura of the role. That said, he negotiated the pasaggio, where so much of the role sat for him, with confident ease. His assumption of the role was robust and forthright for much of the evening, so that when the moment came to express his love to Hanna, it was done with an extrovert account of ‘Lippen schweigen’.

Borgioni sang Camille’s music with his customary beauty of tone. Indeed, he made his entreaties to Valencienne full of buttery beauty, the lines so quintessentially Italian and full of handsome tone. Borgioni has that kind of musicality that cannot be taught, that ability to spin magical phrases full of meaning, combined with one of the most exciting young tenor voices I have heard in a long time. That said, I do continue to have a concern over his management of the top, which still does not sound completely tamed and integrated. I very much hope that Borgioni has good people around him advising and supporting him, since his really is a very special talent – one I hope will thrive as he matures.

Arsenova was a terrifically game Valencienne, giving us cartwheels in her curtain calls. The voice has a delightful fizz on top, while the middle is focused and carries well. Albert Petricca sang Zeta in a bulky baritone with good resonance, while the supporting roles were all competently taken, both in dialogue and in song. The thread throughout the evening was Marco Simeoli’s terrific Njegus. An experienced comic actor, his timing and impeccable delivery of the dialogue, combined with genuine humanity was a sheer delight. The chorus, prepared by Christian Starineri, sang with confidence and precision of ensemble, while dispatching the stage movements with unanimity.

This was a tremendously uplifting evening in the theatre and by far the best I’ve had in my visits to Macerata. We were given a staging full of humanity and humour, spectacle and fun, one that was intelligently staged and ideally paced. The conducting also managed to conjure up a remarkable variety of orchestral colour, even in this challenging acoustic, while the singing was always honest. The audience responded at the close with generous cheers.

[…] OPERATRAVELLER: Segundas oportunidades: Die lustige Witwe en el Festival de Ópera de Macerata […]

[…] OPERATRAVELLER: Segundas oportunidades: Die lustige Witwe en el Festival de Ópera de Macerata […]