Offenbach – Les Contes d’Hoffmann

Hoffmann – Michael Spyres

Olympia/Antonia/Giulietta/Stella – Amina Edris

Nicklausse/La Muse – Héloïse Mas

Andrès/Cochenille/Frantz/Pittichinaccio – Raphaël Brémard

Le conseiller Lindorf/Coppélius/Le docteur Miracle/Dapertutto – Jean-Sébastien Bou

Spalanzani/Nathanaël/Le Capitaine des sbires – Matthieu Justine

Luther/Crespel – Nicolas Cavallier

La voix de la tombe – Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo

Schlémil/Hermann – Matthieu Walendzik

Ensemble Aedes, Orchestre philharmonique de Strasbourg / Pierre Dumoussaud.

Stage director – Lotte De Beer.

Théâtre national de l’Opéra-Comique, Paris, France. Saturday, September 27th, 2025.

This new production of Les Contes d’Hoffmann at the Opéra Comique, coproduced with the Opéra national du Rhin, the Wiener Volksoper and Reims, is a homecoming for Offenbach’s opera. It was within these very walls that the work was first heard in 1881, although without the Giulietta act. I must admit to some considerable excitement at the prospect of hearing this masterpiece in such a historic and intimate space, and right from the opening measures, there was a visceral impact to the music-making that just grabbed one’s attention and refused to let go for the next three hours.

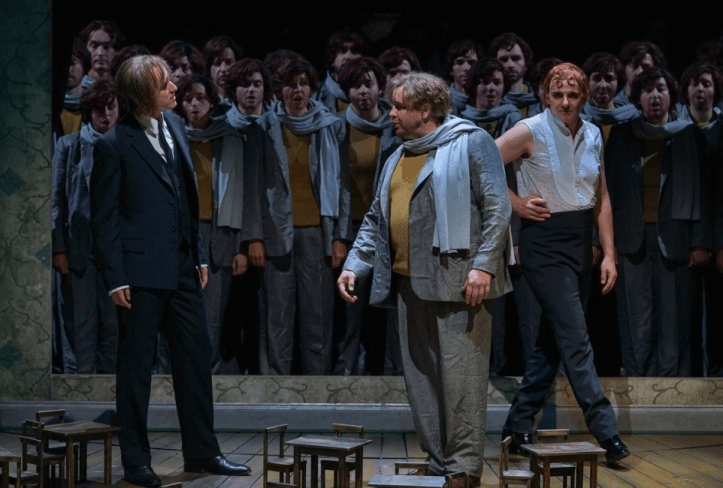

The staging was confided to Lotte De Beer, a director I’ve previously found to be frustratingly inconsistent. I can happily report that this is by far the most successful staging I’ve seen by her. De Beer sets the action within a defined set, which is frequently updated as each act goes by to provide furniture that reflects the action taking place. Rather than the usually-heard recitatives, we instead had the dialogues, here rewritten by Peter te Nuyl and translated into French by Frank Harders. Of course, one might fear that the dialogues could hold the action up, but it’s testament to the cast and the direction that this was never the case. Instead, they were ideally set in the musical context for the evening, the hours passing by like minutes.

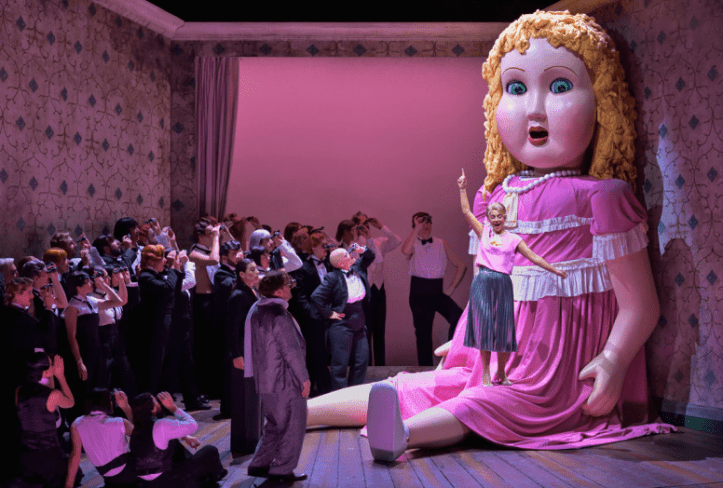

And yet, I must admit to not being absolutely convinced by the new dialogues within the structure of the evening as a whole. Right from the start, there was a sense that De Beer wanted to take a somewhat twenty-first century, revisionist view of Hoffmann. There were constant references to a man who was so self-obsessed, he fell in love with any woman and automatically assumed that those women would be equally obsessed with him. That does feel like a valid reading. Yet I couldn’t help but feel there was a facetiousness to De Beer’s view of the work that lacked sincerity. It felt played for laughs rather than a deeper exploration of the impact of alcoholism or the struggles of creativity, for example. Take the Olympia act. There, she was clearly a doll that, thanks to the magic lunettes, Hoffmann was unable to see her true nature. The stage alternated between having a small doll for Hoffmann to engage and dance with, and a giant one planted on stage, while Olympia’s music was sung by a human with whom Hoffmann refused to engage. Yes, we were given a sense of the ridiculousness of Hoffmann’s obsession with the doll, yet it felt that this was played much more for laughs than trying to take us deeper into his psyche.

That doesn’t mean that De Beer’s staging lacked some interesting visuals. The Antonia act was particularly striking, the stage covered with frames surrounding empty black spaces, through which Antonia stepped to join her mother. Similarly, in the Giulietta act, there was a violence in the interactions that pointed to Hoffmann losing control in a much more ferocious way than I’ve previously seen. The biggest strength of De Beer’s staging is its vivid personenregie. No standing and delivering here, rather a real sense of people genuinely engaging with each other, creating drama of sincere impact. I found the closing scene to be particularly interesting. This is a moment that always moves me immensely, particularly if I think back to Warlikowski in Brussels or Michieletto in Venice, both of whom gave us deep meditations on the power of creativity. Here, it felt that De Beer wanted to give us the conclusion of a journey into self-acceptance, but I have to admit that it didn’t quite convince. Perhaps it was as a result of the perceived facetiousness elsewhere, meaning that any sincerity felt less than genuine. Still, in terms of the personenregie, clarity of vision, and interaction between the characters, this is undoubtedly the best I’ve seen from De Beer to date.

Musically, however, this was almost an unqualified triumph from start to finish. I’ll get the single reservation out of the way first. Given the vocal demands, it’s exceptionally difficult to find a singer who can do justice to all of Hoffmann’s ladies. Amina Edris was certainly a striking stage presence, able to incarnate the showgirl Giulietta and the serious, restrained Antonia. Vocally, however, this assignment was a stretch too far for Edris’ current vocal means. Her Olympia did give some satisfaction, she found a poetry in the melismatic lines, embellishing her song with a good legato, accuracy and a decent stab at a trill. Antonia was a bit more of a stretch. The voice sounds rather narrow, emerging with determined focus. There was a sense, to my ears, that she was pushing the voice more than it could naturally go. Giulietta was certainly the happiest match vocally for Edris, which she sang with thoughtfulness and generosity.

Similarly, Hoffmann is a major challenge for the tenor who takes him on. Particularly as the evening builds up to the most demanding part vocally in the last twenty minutes during the Giulietta act. First off, I have to say that Michael Spyres’ sung and spoken French is very good. Indeed, diction across the entire cast was crystal-clear, making the work live in a way that one so rarely hears. His tenor is bright and focused, able to find meaning in the words, and he was dramatically fearless. Perhaps understandably, I did have a sense that he was pacing his way through the evening – given the length of the role that’s perfectly understandable. That did mean he had enough in the tank for the Giulietta act, even if the very highest reaches needed careful management. Spyres filled his ‘ah vivre deux’ with love and affection, even if it was phrased to a tiny doll, and his Kleinzack had plenty of swagger.

Héloïse Mas was physically tireless as Nicklausse/La Muse. She sang and acted the role with the utmost confidence. Her mezzo has a wonderful claret warmth in the middle and bottom, and while the top does lose some resonance, her diction is so completely and utterly clear that one simply hung off every word she sang and spoke. She sang her ‘Vois, sous l’archet frémissant’ with uninhibited generosity, long lines and soaring ease. A most enjoyable assumption. Jean-Sébastien Bou gave us a highly compelling group of villains. Rather than ‘scintille diamant’ as Dapertutto, he was given ‘Tourne, miroir, which he sang with extroversion, never succumbing to the urge to hector. Indeed, his baritone was agreeably firm and focused throughout, from top to bottom, rising to the challenge of each role. The remainder of the cast reflected the excellent standards one would expect at this address. Replacing the originally cast Marie-Ange Todorovitch at the very last moment, Sylvie Brunet-Grupposo sang the Voix de la tombe with her customary warmth and amplitude. Nicolas Cavallier was a stentorian Crespel, singing his music in a rustic bass. Matthieu Justine was a deliciously sardonic Spalanzani, the words nicely forward, while Raphaël Brémard sang Frantz’s arioso with delicious wit.

The biggest triumph of the evening for me was Pierre Dumoussaud’s conducting and the playing of the Orchestre philharmonique de Strasbourg. He led his musicians in a delectably swift reading of the work. Indeed, this must be the best-conducted Hoffmann I’ve ever experienced in the theatre. There was a lightness of approach, a rhythmic impetus, that just swept the evening along with unfailing sureness. Yet Dumoussaud also allowed the music space to tell its full story, pulling back in ‘Elle a fui, la tourterelle!’, to allow that glorious melody the languid space it needed. Attack in the strings was sharp and tight, with minimal vibrato used to emphasize emotion. This did mean that some of the very highest writing in the violins in the Olympia act did have some passing moments of sourness, but these were brief. The horns played with genuine poetry and accuracy. This was superb orchestral playing. As was the singing of the Ensemble Aedes, prepared by Mathieu Romano. They did sound slightly taken by surprise at the very start of the evening, falling slightly behind the beat, but once past that they sang with unfailing ensemble, rhythmic accuracy, luminous tone and impeccable diction.

There was so much to enjoy in tonight’s Hoffmann. Yes, I have some high-level reservations about De Beer’s staging, which felt a bit too self-consciously clever, verging on facetious. What it did do, however, was tell a very clear story, with compelling and believable personenregie. Edris’ was also a watchable actress, if somewhat vocally stretched by the demands of the roles. The remainder of the evening, however, gave an enormous amount of pleasure. The drama lived through the clarity of the diction; Spyres, Mas, and Bou were particularly excellent, and Dumoussaud’s conducting and the playing of the orchestra were superb. The audience responded at the close with generous and long-lasting applause.

[…] was delighted to return to the Opéra Comique after a number of years, to see Les Contes d’Hoffmann in the theatre where it first saw the world. Michael Spyres was perhaps suffering from an […]