Donizetti – Lucrezia Borgia

Don Alfonso – Krzysztof Bączyk

Donna Lucrezia Borgia – Marina Rebeka

Gennaro – Duke Kim

Maffio Orsini – Teresa Iervolino

Jeppo Liverotto – Jorge Franco

Don Apostolo Gazella – Pablo Gálvez

Ascanio Petrucci – Julien Van Mellaerts

Oloferno Vitellozzo – Cristiano Olivieri

Gubetta – Matías Moncada

Rustighello – Moisés Marin

Astolfo – Alejandro López

Coro Teatro de la Maestranza, Real Orquesta Sinfónica de Sevilla / Maurizio Benini.

Stage director – Silvia Paoli.

Teatro de la Maestranza, Seville, Spain. Saturday, December 6th, 2025.

This evening’s performance of Lucrezia Borgia at the Teatro de la Maestranza in Seville, was my first performance at this handsome theatre in over a decade. I really should visit more often, since they offer a stimulating program of opera, with judicious casting and high musical standards. The runs do tend to be rather short, however. Silvia Paoli’s production, shared with Tenerife, Oviedo and Bologna, is only running for three performances, of which tonight was the second. The biggest interest in this run was the presence of Marina Rebeka in the title role and experienced bel canto conductor, Maurizio Benini, in the pit.

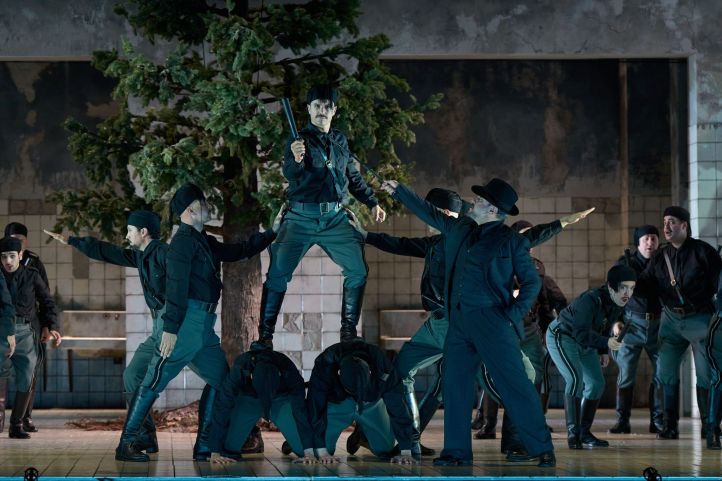

Paoli sets out on her production with an interesting premise. La Borgia is known as a fierce woman, one who had significant impact on the lives of Gennaro’s friends and their families. What Paoli attempts to do is humanize Lucrezia, attempting to explain where her murderous search for power emerged from. The evening opens with a tableau accompanying the opening measures, showing a young girl at home with an adult male, presumably her father. Paoli suggests that the girl is a victim of abuse, in turn influencing Lucrezia’s future life. Indeed, it did make me wonder whether Paoli was similarly suggesting that Gennaro was a product of the abuse, and that Lucrezia’s search for him and attempt to reconcile was her coming to terms with her past. It’s certainly a thoughtful starting point for an exploration of the work. Around Lucrezia, Paoli sets an environment of violence and horror. Don Alfonso keeps a group of women in a cage, who he also abuses, stringing one up and shooting her after his big scene. Similarly, Gennaro and his friends are black shirts, presumably equally violent, and Paoli also suggests, though doesn’t show, that they inflict a gang rape on Lucrezia at the end of the prologue. Indeed, the party in Venice is accompanied by courtesans who accompany Orsini’s opening narration by dry-humping some men on chairs. The set, by Andrea Belli, is a wide-open industrial space, redolent of an abattoir, where blood on the wall sets the scene for an evening of frequent violence.

Paoli’s staging is certainly visually impactful, but also significantly problematic. She choreographs the extras quite significantly, so that they often perambulate around the stage during the duets. Yet her direction of the principals more than often feels perfunctory, frequently/ left to resort to stock operatic gestures. Moreover, their placement on stage wasn’t always optimal. The acoustic of the Maestranza is warm and resonant for the orchestra, yet from my seat in row 12 of the Platea, when the principals were at the back of the set, the sound was too recessed, impacting audibility. I’m also not quite sure why Paoli had the chorus in Act 2 simulating exercise moves, but they were certainly game and got into the spirit of things. Paoli clearly has a vision of how she wants to present the work, her staging starts from a sensible starting point, and she has clearly thought deeply about the characters within, choreographing the action. Yet, that depth of thought didn’t, to my mind, manifest itself in the way she directed the principals. I longed for her to take the extras off the stage and instead allow us to focus on the characters. I also wish she’d developed the Gennaro/Orsini relationship more, the queer subtext not even attempted to be explored. That said, she did give Lucrezia the opportunity to hold the stage alone in her final scene. However, compared to Andrea Bernard’s staging in Florence last month, I found Paoli’s staging to be thoughtful yet lacking in focus on the principals.

Benini achieved some terrific playing from the Real Orquesta Sinfónica de Sevilla. The off-stage band seemed to have been caught off-guard by the zippy tempo in the opening scene, but they settled down quickly. I appreciated the piquancy of the trumpets and the winds were nicely mellifluous. Benini’s reading was based in tempi that felt utterly natural, always elastic and moving with the ebb and flow of the music, giving his principals space to weave their lines, yet never compromising rhythmic impetus and forward momentum. Of course, I did wish that he has asked his strings to play with shorter bow strokes and without vibrato, but this is of course personal taste – although the depth of string tone he did obtain from the band was full of colour. Indeed, Benini showed himself as a master of orchestral colour here, the ethereal sound he achieved from the strings as Gennaro expired was most impressive. The chorus, prepared by Íñigo Sampil, was terrifically lusty, nicely tight in ensemble, and had some impressively focused and warm tenor tone.

This was my third Lucrezia Borgia this year, having seen Lidia Fridman in Rome and Jessica Pratt in Florence. Rebeka demonstrated singing of the finest quality tonight. She managed to make those long, Donizettian lines sound easy: the endless phrases on the breath, the limpid float on high and the immaculate coloratura might sound so effortless, but they belie the hours of work in the studio that go into such an impressive technique. Rebeka was always utterly musical, singing with focus and precision, filling the text with meaning. Her diamantine tone was utterly even from top to bottom, emerging from a rich chestiness, to acuti that shone into the room with focused brilliance. Her opening ‘com’è bello’ was sung with poise and evenness, soaring with ease. In her final scene, she added some daring and always scrupulously musical variations, capping the evening with a thrilling high E-flat. The fact that Benini added a massive ritardando in the coda as we approached the summit might have been gratuitous, but it was utterly tremendous and, as Rebeka held onto the height for a considerable time, it sent the audience wild. More than anything, Rebeka gave us a singing lesson tonight.

Teresa Iervolino made so much of Orsini’s music. As with Rebeka, she understands how this music should go, filling Orsini’s narrations with drama and musicality. Her rich contralto turned the corners with ease, filling out the textures with a Barolo-red tone. She made Orsini’s contributions utterly compelling in a way I’ve never experienced before. Duke Kim brought a focused, bright tenor to Gennaro’s music. Perhaps it was nerves that resulted in a lack of support in this first duet with Lucrezia, as he certainly rallied thereafter. Kim brought a scrupulous and well-schooled attention to the line, with an admirable legato, and he had obviously worked on making the text comprehensible. And yet, undoubtedly as a result of the direction of the principals in the staging, I did find his singing to be more on the anonymous side, certainly decently sung and studied, but I longed for him to unite text, drama and music more.

I had a similar impression of Krzysztof Bączyk’s Don Alfonso. He sang the role superbly, with genuine beauty of tone and a rich, handsome bass, bringing a real bel canto sensibility to his music. This was, however, in opposition to his character and the way he was staged. While we saw a brutal dictator who strung semi-naked women up and shot them, what we heard was a beautifully sung and stylish piece of bel canto. While his Italian was very clear, it struck me that Bączyk could perhaps have coloured the words more to bring the violence of his character to the fore. The remainder of the cast reflected the admirable standards of the house. Pablo Gálvez and Julien Van Mellaerts brought their handsome baritones and firm tone to the roles of Gazella and Petrucci. Matías Moncada sang Gubetta’s music in a warm, rich bass, while Moisés Marin’s focused, textually-aware singing gave pleasure as Rustighello.

There was much to enjoy in this evening’s Lucrezia Borgia. Paoli’s staging did attempt to provide a cogent framework for the action to take place in, although I’m surprised that the house did not warn spectators of the treatment of sexual abuse in the staging, nor did they provide signposting to sources of help should any abuse survivors have been triggered by what they saw. Musically, there was so much to enjoy, with Benini’s conducting guiding the evening with a sure hand and Iervolino, in particular, giving Orsini so much depth of vocalism and characterization. Rebeka was marvellous, singing with a fabulous bel canto technique, sending the audience home on a high. The public responded at the close with generous ovations for the entire cast, rising to its feet with a wall of cheers as Rebeka took her curtain call.

[…] of herself. She also had the benefit of a superb staging by Andrea Bernard. In Seville, Marina Rebeka gave us a singing lesson, demonstrating a fabulous technique always at the service […]