Verdi – Ernani

Ernani – Antonio Poli

Don Carlo – Amartuvshin Enkhbat

Don Ruy Gomez de Silva – Vitalij Kowaljow

Elvira – Olga Maslova

Giovanna – Elisabetta Zizzo

Don Riccardo – Saverio Fiore

Jago – Gabriele Sagona

Coro Fondazione Arena di Verona, Orchestra Fondazione Arena di Verona / Paolo Arrivabeni.

Stage director – Stefano Poda.

Teatro Filarmonico, Verona, Italy. Sunday, December 14th, 2025.

With today’s premiere of this new production of Ernani, by Stefano Poda and conducted by Paolo Arrivabeni, I was making my first visit to the beautiful Teatro Filarmonico in Verona, little brother to the legendary Arena. It’s a beautiful house, with a warm and rich acoustic for the orchestra but, from my seat at the back of the Platea, not always as ideal for the voices. Poda is of course known for his visually spectacular productions at the Arena. I saw part of his Aida a few years ago, and it worked really well in that spectacular space. However, an opera with a complicated plot and in a smaller theatre is a different challenge for a director known for spectacle, and I was intrigued to know what he would do with the work.

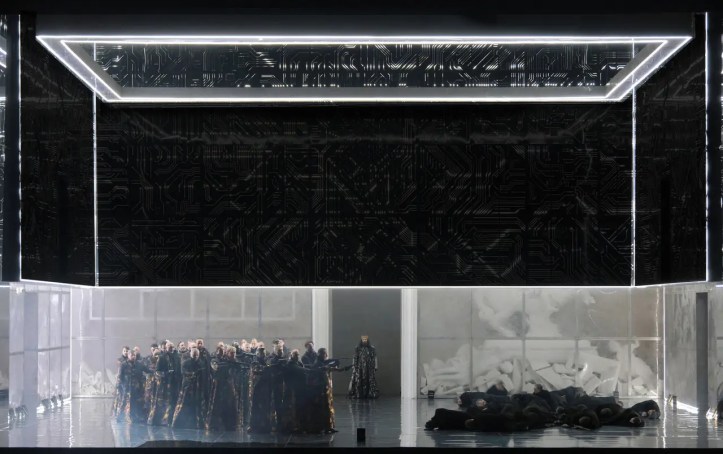

It’s clear that Poda is taking a very stylized, visual approach to the task in hand. The set for the first half of the evening, with the intermission placed after Act 2, is spare, the stage populated within a triangular shape, with statues hidden behind gauze at the back and a video screen occasionally showing some random imagery as well as the letters ‘La bataille d’Hernani’. It was certainly an intriguing setup, although the fact that the screen appeared to be malfunctioning from time to time gave it a slight sense of hazard. The cast was costumed, also by Poda, in long flowing outfits, with Carlo later becoming bedecked with jewellery to reflect his imperial status. Poda had his cast move around the stage in formation, which was less than ideal as much of what they sang was at the back of the stage, meaning that they were less than ideally audible. Indeed, in the Act 1 finale it was hard to hear the principals and chorus over the orchestra. Poda seemed to be telling us something about books, since characters were frequently engaged in reading them. Perhaps he was attempting to explain that this is a story that abounds in further backstories and, by reading them, the characters were educating themselves about them. That would tie in with Carlo reflecting on his imperial predecessors. And yet, the characters informing themselves did not particularly help the audience make sense of the plot. Indeed, there seemed to be a disassociation from what we saw with what we heard in the text.

That isn’t to say that Poda didn’t give us some spectacular visuals. The fact that Carlo gave his big Act 3 aria in front of destroyed statues that had taken over the stage, was certainly striking to look at. Similarly, having Ernani entombed in a large Perspex structure in the final scene was also quite telling. And yet, the fact that Poda preceded that scene with a group of extras entombed in said structure during the trio at the start of Act 4, made it hard to understand what Poda was aiming to represent. Furthermore, in the earlier acts, having the male-identifying characters wearing similar clothing might have been a way to try and portray their similarities; however the effect was the confuse the narrative further – and this is a work I know well. If I found it confused, I would hate to think what a newcomer to the opera might make of it. The direction of the principals was very much based in the tradition of standing and delivering, all while declaring love and not looking at the object of one’s affection. Still, I would maintain that Poda had thought carefully about the work and what he wanted to show us, it’s just that it didn’t manifest itself into a coherent and logical piece of storytelling.

Musically, there were some rewards. The orchestral playing was indeed very good under Arrivabeni’s direction. Thanks to the warmth of the acoustic, there was a wonderful cantabile reach to the sound that was most beguiling. He encouraged a thick pile carpet of string sound, while the winds were particularly characterful. His tempi were generally of the congenial, middle of the road kind, although the evening did finish five minutes early, coming in at two hours and forty minutes, including a twenty-minute intermission. Ornamentation, essential in this repertoire, was absent from the vocal lines. The chorus, prepared by Roberto Gabbiani, of course are given some fabulous moments in the score by Verdi. They sang with enthusiasm and good blend, but were not always helped by their positioning on stage.

The last time I heard Olga Maslova was as Turandot at the Maggio, so I found her to be surprising casting for Elvira. She’s clearly a diligent singer and had worked hard on the style. The voice is founded in a rich chestiness, and rises up to a shining top. She coped well with the coloratura of her ‘Tutto sprezzo che d’Ernani’, even if she doesn’t quite have a genuine trill. Again, Maslova wasn’t helped by her placement on stage, in that Act 1 finale I could see her mouth moving but couldn’t hear her, but when she was brought to the front of the stage, the voice had good size and reach. Antonio Poli continues his survey of the Verdi tenor roles with this assignment. Perhaps he hadn’t quite fully warmed up in his opening number, since the voice sounded pushed to sound artificially bigger, with a fair bit of heavy lifting, the tone wiry. As he progressed through the evening, he gave some really satisfying soft singing in his declarations of love to Elvira. It made me wish that he’d taken his foot off the gas more, because when he pulled back on the volume, it was a really attractive sound. At the close of the evening, he sang with generous force and genuine feeling.

Amartuvshin Enkhbat brought his big, bulky baritone to the role of Carlo. He’s capable of some wonderfully full, long lines, but there’s also a tendency for aspirates to enter the line and also for the pitch to dip. That said, the size of the voice, the stentorian tone and evenness of emission were most impressive. He even brought a sense of genuine introspection to his Act 3 aria – which received the biggest applause of the evening. Vitalij Kowaljow brought his big and still juicy bass to the role of Silva. He darkened the tone quite malevolently to portray Silva’s singlemindedness in the final scene. The remaining roles, Elisabetta Zizzo as Giovanna, Saverio Fiore as Riccardo, and Gabriele Sagona as Jago, were all confidently taken.

It was a pleasure to visit this beautiful theatre, which had been delightfully bedecked for the holiday season in the lobby. I do wonder whether it would have been more acoustically satisfying higher up, given the fact that the sound was very orchestra-heavy from my seat. Poda’s staging was undoubtedly a very visual one, although it was also one that didn’t illuminate the narrative in the way one might have hoped it would. Musically, we heard some excellent orchestral playing, congenial conducting and some decent singing. The audience response at the close for the orchestra, chorus, principals and Arrivabeni was generous. Poda and his team came out to a wall of boos.

[…] satisfaction. Before doing so, I’d like to highlight what was the turkey of 2025. The Ernani I saw in Verona, was something of a mess. Musically, it was decent enough, but Stefano […]