Strauss – Die Frau ohne Schatten

Der Kaiser – Benjamin Bruns

Die Kaiserin – Simone Schneider

Die Amme – Evelyn Herlitzius

Der Geisterbote – Michael Nagl

Ein Hüter der Schwelle des Tempels – Josefin Feiler

Erscheinung eines Jünglings – Kai Kluge

Stimme des Falken – Josefin Feiler

Eine Stimme von oben – Annette Schönmüller

Barak, der Färber – Martin Gantner

Sein Weib – Iréne Theorin

Der Einäugige – Danylo Matviienko

Der Einarmige – Andrew Bogard

Der Bucklige – Torsten Hofmann

Dienerinnnen, Kinderstimmen, Stimmen der Ungeborenen – Alma Ruoqi Sun, Kyriaki Sirlantzi, Fanie Antonelou, Jutta Hochörtler, Deborah Saffery, Itzeli Jáuregui

Die Stimmen der Wächter der Stadt – Torsten Hofmann, Danylo Matviienko, Michael Nagl, Andrew Bogard

Kinderchor der Staatsoper Stuttgart, Staatsopernchor Stuttgart, Staatsorchester Stuttgart / Cornelius Meister.

Stage director – David Hermann.

Staatsoper, Stuttgart, Germany. Sunday, November 5th, 2023.

For a work that makes such extreme demands on its interpreters, performances of Die Frau ohne Schatten seem to be proliferating these days. Alongside this new production at the Staatsoper Stuttgart, there have been performances recently in Vienna, Cologne, and Lyon, with Dresden also premiering a new production in the spring. This new Stuttgart production was confided to David Hermann, a director whose previous work I have greatly enjoyed, starting with a Troyens in Karlsruhe around a decade ago. Together with this mouthwatering cast under the direction of music director Cornelius Meister, I had very high hopes for this evening’s performance.

Of course, Frau has some issues, both in the demands it puts on the cast as well as its rather heavily symbolic and heteronormative libretto. To counter this, Hermann sets the action in a futuristic space, perhaps influenced by the idea of the Mondberge in the libretto, with the events of the plot seeming to evolve in a galaxy far, far away. The sets, by Jo Schramm, alternate between the bright, almost clinical world of the Kaiser and Kaiserin, and an impressive, cavernous space, inhabited by Barak and his family, that appears to be a bunker far below. During Act 1, there’s the presence of what looks like a mechanical millipede that occupies the centre of the stage, evolving to become a bed in which Barak sleeps at the end of the act. This creates a very clear distinction between the two worlds, with the futuristic costumes (also by Schramm) giving an air of fantasy that works well with the content of the libretto.

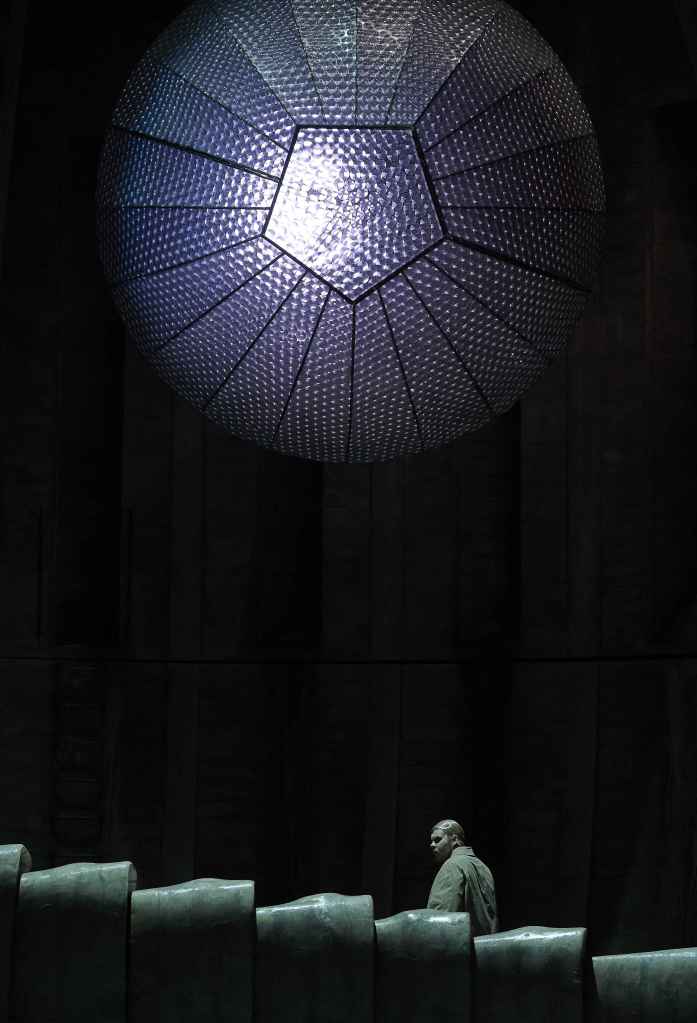

I found Hermann’s personenregie to be inconsistent. There were flashes of genuine human interaction – the relationship between Barak and his wife was clearly conflicted, as one might expect. Yet far too often, characters emoted to the front when they were singing to others. The almost constant presence of the Geisterbote also reflected the ubiquitous influence of Keikobad on the events in the plot. There was a particularly striking moment where the Kaiserin confronted Keikobad in Act 3, with Keikobad seen as a globe descending from the skies, the colours of the light in the globe changing into a warm glow when the Kaiserin refused to become human by robbing the Baraks of their humanity.

In many respects, Hermann’s is a relatively conventional staging that takes the story at face value and illustrates it appropriately. I was thinking throughout that I wished he would question the work’s heteronormativity, to be a little more radical, though with a musical performance as strong as this, the staging did what it needed to do. Then, in the last five minutes the production took a completely different direction. For a moment, it seemed that Hermann was engaging with the problematic heteronormativity of the libretto, which brought a smile to the face when combined with Strauss’ glorious score. Then, Hermann did something that was, for me at least, completely unexpected, that negated both what we heard from the score and the positive uplifting that the closing pages of this work would lead us to expect. I’m not going to put any spoilers here, since the production will be streamed and I would greatly encourage readers to watch it. It’s just that what he did, felt cynical and dark. It was also problematic because the impact of that magnificent closing ensemble was robbed due to the placement of the singers on stage, meaning they weren’t able to bathe us in waves of sound, as had previously been the case in the evening, but also that the elevating spell of the music had been broken. I have no issues if a director wants to take us in a different direction, if that had been set up and threaded through the entire evening. Here, it felt like an unexpected add-on, although having watched it, you might well have expected it.

Musically, though, this was an absolutely spectacular evening. Meister led an orchestra on glorious form. There’s something about this acoustic that’s very special, feeling the floor vibrating under one’s feet during those big Straussian climaxes – and with some of the biggest voices around on stage, there were plenty of those. Meister obtained such a sophisticated tonal palette from his orchestra, the darkness of the menacing lower brass, the piquant winds, and silky strings. He knows how this music should go, bringing out the searching longing to the fore, but also knows how to support his singers, giving them enough of a cushion of sound over which to take wing, but never covering the voices. His tempi felt sensible throughout, not afraid to pull back where needed, and the four and a half hours flew by as if in an instant. The way that he ‘voiced’ the orchestral parts, allowing the multi-textual sound world to seem so clear, was seriously impressive. The choruses, singing from off-stage, sang with precision, with the adults, prepared by Manuel Pujol, making an appropriately sepulchral halo, while the children, prepared by Bernhard Moncado, were nicely cheerful.

Simone Schneider gave us a glorious Kaiserin. As far as I can recall, this was my first time hearing Schneider, and she is a Straussian soprano of rare distinction. The voice has splendid amplitude, with a steely inner core, surrounded by a glamorously creamy exterior. The top opens up thrillingly, with seemingly unlimited height. She filled the long melismas of her opening scene in Act 1 with genuine beauty. Her diction is impeccably clear, but I did wonder if Schneider could do more with the words, to fill them with even more meaning – but this is a very minor thing. She did communicate and understand what she was singing and the power on top is really impressive.

And we most definitely got power with Iréne Theorin as the Färberin and Evelyn Herlitzius as the Amme. The closing pages of Act 2, with both Theorin and Herlitzius going for it was deliciously loud, so much I felt rather windswept. Here was perhaps the only point in the evening where I felt Meister to be a little too contained, he really did not need to hold back with these ladies on the stage. As with Schneider, Theorin’s voice really blooms on top, which she did with easy amplitude. Her Färberin was a fully-created character, truly lived through the text, bringing out the conflict of her character’s journey with genuine immediacy. Theorin did approach the lower range of the voice quite gingerly, the tone down there a little cloudy, but her Färberin was one of real soul and honestly sung throughout. Herlitzius brought her familiar textual intelligence to the Amme, descending to the depths with ease and negotiating the angular writing as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Of course, she was able to pull out the volume where necessary, the top shooting out into the auditorium with theatre-filling magnificence, yet her portrayal of the Amme was much more complete than that. One genuinely gained a sense of the complexity of the character, the care that she felt for the Kaiserin, but also the mischievousness at the heart of the character’s actions. Herlitzius gave us a very complete assumption.

Benjamin Bruns also gave us a fabulously-sung Kaiser. Marking another step into the heavier repertoire, Bruns sang with genuine beauty of tone and long lines. His tenor is well placed and bright in sound, everything sung off the text, able to soar up with impressive ease. Bruns most definitely has a bright future in those more lyrical Heldentenor roles. Martin Gantner’s baritone also sits quite high as Barak. The tone itself is slightly acidic but does have good resonance further down. He sang his ’Mir anvertraut’ with genuine humanity, phrasing it with a lieder singer’s attention to text.

The remaining roles reflected the excellent quality one has come to expect here. Michael Nagl gave us a wonderfully masculine and firm bass-baritone as the Geisterbote, I hope one day to hear his Barak. Josefin Feiler’s bright, crystalline soprano brought genuine beauty of tone to her roles, while Annette Schönmüller brought a distinctive mezzo to the Stimme von oben. Kai Kluge sang the interventions of the Erscheinung eines Jünglings with a bright, lyrical tenor. We also had a very well-blended trio of brothers for Barak, with Danylo Matviienko jumping in at the last moment as the Einäugige, looking (and sounding) as if he had been rehearsing this staging for months with his castmates.

Musically, this was a superlative evening, with outstanding singing across the board and an orchestra on remarkable form, led by a conductor who truly understands this music. The staging, for the most part, worked well, but just lost its way in the closing moments. Indeed, I’m still trying to comprehend why Hermann took it the way he did – is he trying to give us a reflection on the world we leave for those who come next? Is it simply a fairytale turned dark? I genuinely don’t know. What I do know, is that it seemed to come from nowhere and went against the grain of what we heard without having been prepared through the course of the evening. A shame, because musically this is a Frau that has to be heard. The audience gave the entire cast a generous ovation at the end of each act with huge cheers at the final curtain.

[…] Salome was truly superhuman in her vocal power and stamina. In Stuttgart, I saw a Frau ohne Schatten, conducted with genuine insight by Cornelius Meister. The great Evelyn Hertlizius made the […]