Rimsky-Korsakov – The Tale of Tsar Saltan (Сказка о царе Салтане)

Tsar Saltan – Ante Jerkunica

Tsaritsa Militrisa – Svetlana Aksenova

Tkachikha – Stine Marie Fischer

Povarikha – Bernarda Bobro

Babarikha – Carole Wilson

Tsarevich Gvidon – Bogdan Volkov

Tsarevna Swan-Bird – Olga Kulchynska

Old man / Shipman – Alexander Kravets

Messenger / Shipman – Nicky Spence

Skomorokh / Shipman – Alexander Vassiliev

Koor van de Munt, Orchestre symphonique de la Monnaie / Timur Zangiev.

Stage director – Dmitri Tcherniakov.

La Monnaie – De Munt, Brussels, Belgium. Sunday, December 3rd, 2023.

For its last production of 2023, La Monnaie – De Munt has revived Dmitri Tcherniakov’s 2019 staging of Rimsky-Korsakov’s rarely seen The Tale of Tsar Saltan. A co-production with the Teatro Real, the production won the International Opera Award for Best Staging in 2020. As one might expect with Tcherniakov he doesn’t give us a conventional reading of the narrative. Instead, what he gives us is incredibly compelling and extremely moving.

In a note in the program book, Tcherniakov mentions how he spends a lot of time reflecting on and analyzing an opera before staging it. Yet, when preparing this Tsar Saltan, the process seemed to flow extremely freely. Based on Pushkin’s poem, this is a story that most Russophones will be extremely familiar with from a very young age – one passed down from generation to generation. Tcherniakov transforms the opera into the story of a mother and her son. A spoken soliloquy by Svetlana Aksenova’s Militrisa at the start of the evening sets the scene. She mentions that her son is autistic and that he is only able to engage with others through the medium of fairy tales. She also mentions that she has never talked to her son about his father, the only man that she truly loved, but feels that this is the time. This sets in motion the events of the opera, through which we see the mother’s life played out, together with her son’s. We initially get a relatively conventional setting of the opening act – complete with traditional Russian costumes. Yet what becomes immediately apparent is that, acted at the lip of the stage in front of a wooden backdrop, we’re very much seeing a fairytale come to life, in the same way that we might see it in a traditional picture book. The contrast between these traditional costumes for the sisters and Babrikha, compared with the constant presence in modern dress of Militrisa and her son, puts this divergence into stark relief, particularly as Bogdan Volkov’s Gvidon reacts constantly to events, presenting someone who, if not perhaps completely non-verbal, does have significant challenges communicating with society.

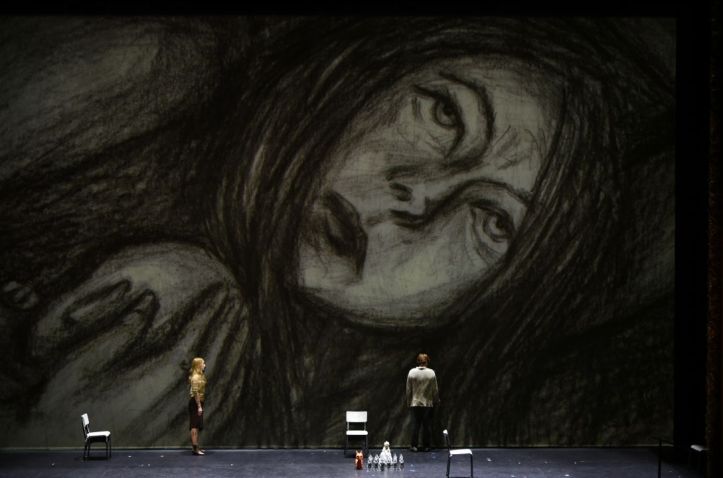

As the evening evolves, we then see the son take over the role of Gvidon. What Tcherniakov, together with Volkov, achieves is nothing short of miraculous. They somehow manage to take us into Gvidon/the son’s mind, showing us the wonder of how he communicates, thereby bringing to life the reality of those among us who are neurodivergent to varying different degrees. Volkov is tireless on stage, constantly moving, bringing to life these incredible images. This is achieved through the use of animation, by Gleb Filshtinsky, with black and white images becoming bright colour, or the image of the Swan transforming seamlessly from animation into reality in the person of Olga Kulchynska. I found it so unbearably moving to watch Gvidon’s conception of the world come to life – it had me in floods of tears. There are a few moments in particular that stand out. At the end of Act 2, as the city of Ledenets came into life, we saw Gvidon draw the city with his hands, manipulating the animation to bring the city to life. While he did this, we saw his mother joining in. She may not have been able to see what he was seeing, but she encouraged him nonetheless, and the love between the mother and son – of someone who doesn’t quite understand her son but loves and supports him deeply – was just such a profoundly beautiful image. Moreover, these visuals amplified Rimsky’s score magnificently at that moment, with the chorus singing from the auditorium, bathing us in sound, and bells pealing – it was glorious. Similarly, in Act 4, where Tsar Saltan met Gvidon, the entire ensemble returned to stage in modern dress, watching Gvidon/the son reacting to his first meeting with his father. Some mocked him, yet the way that Saltan tried to show some love and understanding to Gvidon, to communicate with him through fairy tales was again, deeply moving.

What will stay with me from this afternoon is the sheer humanity and understanding in Tcherniakov’s staging. It’s undoubtedly stunning to look at – though I wish the lady two rows in front of it would have stopped filming it as it was incredibly disruptive to have that in my line of sight for three hours. Yet, as so often, the evening wouldn’t have had the impact it did have, had the musical aspects not been as satisfying as they were in many respects. Timur Zangiev led this superlative orchestra, once again on stratospheric form. The sheer range of instrumental colour he obtained from them was staggering – from a deep-pile carpet of string sound, with muted, dusky strings for the lullaby, or the superb horn playing in some very tricky passages. Climaxes blazed in a golden glow, yet he always allowed his singers through the textures. Those twirling lines of the famed ‘flight of the bumblebee’ were dispatched with virtuosic ease. There were some isolated passages where I felt Zangiev’s direction was a bit plodding and pedestrian, he could certainly have pushed his players to bring out even more rhythmic detail. Nevertheless, this was another occasion on which this orchestra proved themselves as one of the best in the world. The chorus, prepared by Emmanuel Trenque, sang with remarkable precision of ensemble despite their scattered location. The basses added some terrifically resonant descents to the sepulchral depths, while the tone in the sopranos and mezzos was agreeably even.

This was a career-defying performance from Volkov, the kind where one isn’t sure where the real person ends and the character begins. He seemed to be completely inhabiting the role of the autistic son through his physicality, giving us an assumption of raw intensity. Moreover, his tenor sounds in fabulous shape, able to soar with ease, well-placed and bright in tone, using the language to colour the text. Aksenova brought so much humanity to her assumption, the sheer love for her son palpable throughout. I have to say that vocally, Aksenova was somewhat out of sorts – perhaps an unannounced indisposition. The voice had a tendency to curdle, dropping below the note, and was rather chalky in tone. Still, the sheer humanity that she brought to her stage persona gave so much pleasure.

Kulchynska sang her music in a diamond-toned soprano with welcome textual acuity. She did have a tendency to scoop up to higher notes from below and the top lacks somewhat in spin. Yet, she’s also an engaging actor – the scene where the Swan takes on human form and engages with Volkov’s Gvidon/Son and his mother, was another extremely moving moment. As the Tsar Saltan, Ante Jerkunica brought a warm and generously vibrating bottom, while the top loses colour – although he does negotiate it expertly through sheer experience. We also had a terrifically camp pair of sisters from Stine Marie Fischer as Tkachikha and Bernarda Bobro as Povarikha. Fischer made use of a generously full chestiness, while Bobro’s narrower soprano had plenty of character. Carole Wilson brought her considerable stage presence to Babarikha, holding the stage, even when not singing, with her extremely vivid facial expressions. Her mezzo was absolutely even from top to bottom, the registers integrated.

The remaining roles were rather luxuriously cast. Alexander Vassiliev was an energetic stage presence as Skomorokh, his bass focused in tone. Alexander Kravets brought a characterful tenor to the role of the Old Man, also using the text to colour the tone, while Nicky Spence ably negotiated his music as the Messenger.

This is a very special evening. Tcherniakov has given us a staging that explores the love between a mother and a son and allows us to enter into the mind of someone who sees the world differently. Together with his cast, they bring out the fantasy of this story, amplifying the score and heightening its effect, to make us feel and reflect. While some of the vocal performances were a bit rough and ready, the cumulative impact of the music and the acting was immense – especially as the orchestra was, once again, on spectacular form. I’ve had the pleasure of seeing several Tcherniakov stagings over the years, but this may well be his greatest – even more than the Zurich Makropulos. The reception from the audience at the close was generously warm, with an especially touching moment at the very end of the curtain calls, where the three Ukrainian members of the cast – Volkov, Kulchynska and Kravets – took a final solo bow. If you can get to Brussels, run for a ticket.

[…] discussed the staging in some detail in my previous review. Yet seeing it for a second time gave it even more emotional impact. In short, rather than […]