And so, to paraphrase Paul Anka, the end is near of 2023. It’s been a relatively positive year on the whole, with some ups and downs, but overall the year is ending in a much better place than where it started. This year, I travelled further than ever for opera, with the privilege of finally being able to visit the legendary Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. What an amazing city that is, full of life, incredible food and wine, and culture everywhere – by all accounts the city in the world with the highest number of bookstores and theatres per capita. I also had the pleasure of visiting the equally legendary Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, the Opéra de Lorraine in Nancy and the Teatro Regio in Parma, all for the first time.

I started the year in beautiful Florence, with the first of three Don Carlo(s) this year, and my penultimate opera of the year was in València with Maria Stuarda. Both featured Eleonora Buratto in the lead soprano role. I am convinced that Buratto is the finest Italian soprano before the public today. She has a glorious instrument, of strawberries and cream tone, an instinctive sense of line, and impeccable textual awareness. Hers is a very rare talent and I really hope that she has the right people around her guiding her to make the right choices. Any opportunity to hear Buratto in Mozart, bel canto, and the lyric Verdi roles should be grabbed with both hands. The Florentine Don Carlo was somewhat hampered by Daniele Gatti’s extremely slow tempi (I thought we’d still be there this month), but the Maria Stuarda was well cast across the whole, with Siliva Tro Santafé demonstrating a deep understanding of the bel canto style, together with the very promising young bass Manuel Fuentes.

I heard more bel canto through the year, not least the Anna Bolena at the Colón, where Olga Peretyatko was somewhat stretched in the title role, while Daniela Barcellona’s Giovanna Seymour was the best thing I’ve heard from her, complete with a spectacular high C. Xabier Anduaga sang Percy, in his bright, focused tenor – another exceptional talent I hope will be carefully nurtured for a long and successful career. There were two versions of Lucia di Lammermoor this year. Both had in common stagings that were questionable and not entirely successful. In Lisbon, Alfonso Romero Mora, directed a Lucia di Lammermoor that appeared to show little sensitivity to how singers produce sound, with the lovely Rita Marques having to sing her mad scene seated in a car. Luis Gomes gave us a glorious account of Edgardo’s final scene, beautiful phrased while singing lying down. Over in Bergamo, we got Lucie de Lammermoor sung in creditable French. Caterina Sala, who was a glorious Adina there a few years ago, was somewhat stretched by the title role, demonstrating a fabulous natural instrument but a technique that is still very much a work in progress, while Patrick Kabongo’s Edgard was elegantly phrased, but lacked in amplitude.

As always, hearing young artists gives me a great deal of pleasure. In Bologna, I saw an Elisir d’amore that featured the young tenor Valerio Borgioni as Nemorino. He has a gloriously bright instrument, with easy reach. When he first started to sing, I had tears in my eyes because that sunniness to the tone was so deliciously Italian. A name to watch. In Parma, a Matrimonio segreto featured a youthful cast of much promise, under the musical direction of the extremely sensitive Davide Levi. In Copenhagen, I was delighted to see the exciting US mezzo, Raehann Bryce-Davis take on the role of Amneris in a rather risible staging of Aida, rising to a thrilling judgment scene.

2023 feels a bit like the year of Aida, having seen three and a half performances of the opera. The half was in Verona, where I still haven’t managed to see a full performance of the work on the third attempt, although the young Aida there, Mónica Conesa, is a very promising talent. In Berlin, Calixto Bieito gave us a very thoughtful staging of Aida, perhaps lacking in the visceral emotional impact of his earlier work, with Clémentine Margaine sweeping all before her as a magnificent Amneris. In Munich, Damiano Michieletto gave us a similarly thoughtful Aida but one that had real emotional impact, looking at the effects of war on those involved in it. Musically, it was disappointing, with Elena Stikhina’s assumption of the title role far from the kind of standard a house like this should be offering its public. More positive were George Petean’s highly musical Amonasro and Alexander Köpeczi’s handsomely-sung Ramfis. Also in Munich, Dmitri Tcherniakov staged War and Peace in a staging of intricate detail and musically at the highest level. Krzysztof Warlikowski staged a double bill of Dido and Aeneas and Erwartung as the mental processes of a woman suffering the trauma of life as a refugee, brought to life with staggering musical and dramatic insight by the great Aušrinė Stundytė.

Verdi was a constant thread throughout the year. A performance of Don Carlo at the Munich Opera Festival in the summer was appropriately festival quality, with a terrific cast, including Charles Castronovo ardent in the title role, Maria Agresta a generous Elisabetta, and an extrovert Eboli from Clémentine Margaine. In Geneva, Castronovo sang the title role in French in Don Carlos, with a mainly francophone cast, in a staging by Lydia Steier that had some good ideas, with Stéphane Degout a glorious Posa and Ève-Maud Hubeaux an exciting Eboli. I saw two Trovatores. One in Parma, featured Clémentine Margaine again giving us a riveting Azucena, while Riccardo Massi sang a musical Manrico. Francesco Ivan Ciampa’s conducting of the Teatro Comunale Bologna orchestra and chorus was wonderfully idiomatic. Similarly idiomatic was Antonio Pirolli in Lisbon leading a very camp staging by Stefano Vizioli, with Cátia Moreso a exhilarating Azucena and Alessandro Luongo a very musical Luna. Gregory Kunde gave us his deservedly acclaimed Otello in Piacenza, singing with genuine insight and remarkable vocal freshness for a man entering into his eighth decade. Luca Micheletti was a psychologically insightful Jago, singing with such clarity of text. In Hamburg, George Petean once again confirmed his status as one of today’s leading Verdi baritones with an exceptionally moving Simon Boccanegra. As did Quinn Kelsey as Macbeth in Toronto, singing with a glorious legato and sense of line, with Alex Penda a fabulous Lady – even ornamenting her cabaletta – although David McVicar’s staging was rather vacuous. At the Liceu, Sondra Radvanovsky gave us an equally magnificent account of the role of Lady Macbeth in a rather statuesque staging by Jaume Plensa.

Radvanovsky was also a thrilling Turandot in Naples. What a pleasure it was to hear a Turandot who does not take the line ‘quel grido’ literally, instead singing with genuine musicality and seemingly limitless resonance and reach. Yusif Eyvazov was a reliable Calaf and Rosa Feola a beautifully sung Liù. Vasily Barkhatov’s staging I found genuinely insightful, engaging with the difficult aspects of the work, while Dan Ettinger’s conducting failed to keep the disparate forces together. Again in Lisbon, Elisa Cho gave us an incredibly moving account of Madama Butterfly, in a staging by Jacopo Spirei that genuinely attempted to engage with the similarly problematic issues in that score. Over in Florence, Sara Blanch was a glorious Ann Trulove in the Rake’s Progress, singing with such improvisatory freedom, she made it sound easy. Daniele Gatti’s conducting was much more successful here than in the Don Carlo, offering an irresistible rhythmic propulsion which, together with Frederic Wake-Walker’s staging, reminded us that this work is indeed a masterpiece.

Mozart was present, as always, though with only one work this year – the one that’s probably my desert island opera: Le nozze di Figaro. I saw three productions. In Bologna, a youthful Italian cast sang with genuine musicality under the direction of equally youthful Flemish conductor Martijn Dendievel. I found Dendievel’s tempi to be a little on the slow side, but the frequent use of ornamentation, essential in this repertoire, gave much satisfaction. The singing was fabulous across the board. The Scala revived Giorgio Strehler’s historical staging, under Andrés Orozco-Estrada. He gave us a very complete version of the score, with Luca Micheletti’s Figaro absolutely stealing the show with a profound understanding of Mozartian style, including impeccable ornamentation. Only the saggy delivery of the recitatives let the evening down. In Flanders, Marie Jacquot led an interpretation that was delightfully swift. It benefitted from the presence of Kartal Karagedik as the Conte, singing in impeccable Italian. Tom Goosens’ staging, on the other hand, was very much aimed at a local Flemish audience, using performers from outside the operatic tradition as Marcellina and Bartolo/Antonio. I was clearly an exception as the audience seemed to find it all hysterically funny. In Brussels, Stéphane Degout gave us a superbly implacable Yevgeny Onegin, with Sally Matthews giving us the best I’ve heard from her as Tatyana, managing to overcome the intonation issues that have plagued my previous experiences with her. As always, the house orchestra there was superb – in my mind one of the top three opera orchestras in the world currently. As is that of València which, under musical director James Gaffigan, gave us a staggering account of Pikovaya Dama. It was decently cast across the board with Arsen Soghomonyan a remarkable Herman. Richard Jones’ staging looks its age now, but the house chorus was on fantastic form.

As one Ring comes to a close, another begins. In Helsinki, Anna Kelo’s cycle moved forward with Siegfried. This confirmed the qualities of her cycle as seen so far – visually picturesque with much to look at. The cast, made up primarily of local singers, was excellent across the board, as was the house orchestra. Hannu Lintu’s conducting felt somewhat too tight-reined. In Brussels, Alain Altingolu led a house orchestra on simply superlative form in Das Rheingold in a staging by Romeo Castellucci. They didn’t put a foot wrong in the entire score, not even a single split note. The singing was also satisfying. Castellucci’s staging was intriguing, but I found it to be extremely visual to the detriment of character development. That said, there was a performance of staggering physicality from Scott Hendricks’ Alberich, while Marie-Nicole Lemieux made Fricka a much more rounded character than we often see.

Staying with German opera, I saw a trio of Strauss works. In Copenhagen, Dmitri Tcherniakov staged Elektra as a closed domestic tragedy, with Lise Lindstrom tireless in the title role (and without the usual theatre cuts), while Thomas Søndergård conducted an orchestra on sensational form – the other in my top three of best opera orchestras in the world currently. Common to both Tcherniakov’s Elektra and his Salome in Hamburg was the set and Violeta Urmana. As both Klytämnestra and Herodias, she was utterly riveting. Asmik Grigorian’s Salome was truly superhuman in her vocal power and stamina. In Stuttgart, I saw a Frau ohne Schatten, conducted with genuine insight by Cornelius Meister. The great Evelyn Hertlizius made the Amme’s music sound easy, and the close of Act 2 with both Herlitzius and Iréne Theorin’s Färberin going for it was deliciously loud. Simone Schneider sang the Kaiserin with a gleaming top, while Benjamin Bruns was a genuinely lyrical Kaiser. David Hermann’s staging seemed to completely lose its way in the last few minutes, giving us a rather cynical ending that jarred with the uplifting music of those closing pages. Though at least he showed some willingness to engage with the work’s heteronormativity.

There wasn’t much symphonic music this year, although I did manage to see a trio of Mahler 2s and a Mahler 8. The Eighth I saw at the Scala and it was certainly loud. There were some felicitous moments where the sopranos of the Scala and Fenice choruses agreed on pitch, otherwise the choral singing was rather rough. For one of the three Mahler 2s, I had the pleasure of returning to my hometown to see the musicians of the future in the Orchestre symphonique des jeunes de Montréal, with the always radiant Karina Gauvin singing the soprano solo. At the Fundação Gulbenkian, the orchestra and chorus were on blazing form in an inspiring, if not quite note-perfect performance. But it was at the Teatro Nacional de São Carlos that I saw the most transcendental of them this year. Antonio Pirolli brought Italian phraseology to the music, making each of the lines sing. But what Pirolli also knew is that those 70 plus minutes don’t aim for the final chorale, instead they aim for that big moment at ‘sterben werd’ ich um zu leben’, which here was overwhelming. I left the theatre renewed and reminded that whatever life throws at us, we still have some of our best days ahead of us.

As every year, I like to pull out three shows that represent particular highlights of the year. But this year, I’d also like to highlight the opposite. I saw two productions of Tristan und Isolde in 2023. The first, in Nancy, was musically respectable, with Dorothea Röschmann offering her prise de rôle as the Irish princess. However, the staging, by Tiago Rodrigues, consisted of a pair of dancers holding up 950 flashcards as the evening progressed, including such pearls as ‘la femme triste a une amie’ and ‘beaucoup de mots’ whenever a character enumerated loquaciously. It was exasperating. More frustrating, was Philippe Grandrieux’s staging in Flanders. The musical side was actually pretty good. The house orchestra under Alejo Pérez was on revelatory form. Samuel Sakker, as in Nancy, was a relatively small-voiced but textually aware Tristan who more than lasted the course, although it was hard to know what language Carla Filipcic Holm’s Isolde was singing in. As for the staging, well at least I got a lesson in the anatomy of lady gardens, since Grandrieux used the evening to project naked women on a screen the height of the proscenium. One would expect an audacious staging to magnify the score. Yet, here Grandrieux seemed to be working against it, juxtaposing images of a naked woman, seemingly experiencing an epileptic fit, against some of the calmest music in the repertoire during the love duet. Direction of the principals involved Isolde being required to lie on her back, do yoga stretches, or squat as if caught short on a road trip to Cornwall. It was certainly an experience to see it and gave me conversation material for dinner parties for the remainder of the year.

More positively, however, I can report on the three shows that particularly stood out in a year of multiple rewards. At the Gran Teatre del Liceu in February, we were treated to a feast of Händelian singing in Alcina. Marc Minkowski conducted his Musiciens du Louvre with wonderful spirit and the hours just flew by. More than that, it felt like one of those evenings where the bar was raised at the start and just got better and better. Magdalena Kožená sang the title role with an enormous sense of passion and feeling. Erin Morley was a delicious Morgana with impeccable embellishments to the line, while the great Anna Bonitatibus gave us charming calmness in the green fields allied with singing of staggering agility as Minkowski pushed her to even higher levels of virtuosity. Elizabeth DeShong’s Bradamante is the best thing I’ve heard from her, while Alex Rosen’s Melisso was sung in a very handsome bass. The entire evening was simply magical.

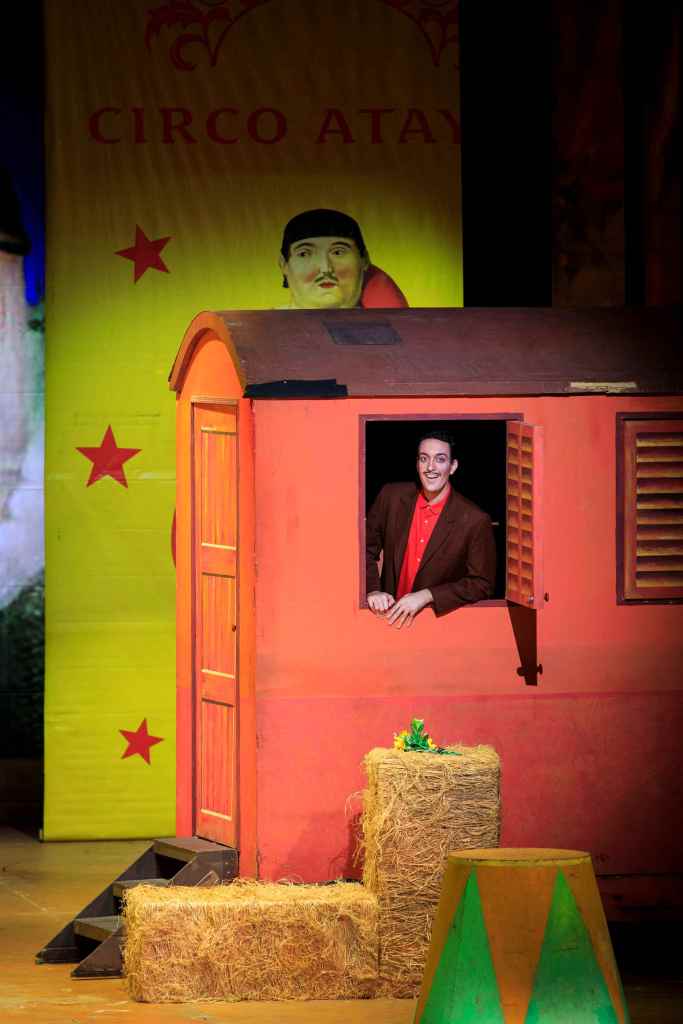

As indeed was les Contes d’Hoffmann at the Fenice. I had the privilege of attending the season opening, complete with the presence of the President of the Italian Republic. On a personal level, simply being there on such a prestigious occasion was an amazing experience, definitely an evening I’ll remember and cherish for a very long time. Fortunately, the show itself was most definitely at that level also. The singing, throughout the cast, was very good, not least the great Véronique Gens as Giulietta and Alex Esposito’s villains. But what I’ll take with me was Damiano Michieletto’s staging, so full of fantasy. The closing tableau, with Hoffmann initially alone and then joined by all the characters his mind had created, was simply glorious, a reminder of the power of creativity of those who might not ‘fit’ into conventional society, but who make our world so much richer as a result. As always, Michieletto knows how to make you feel and here, he most certainly does.

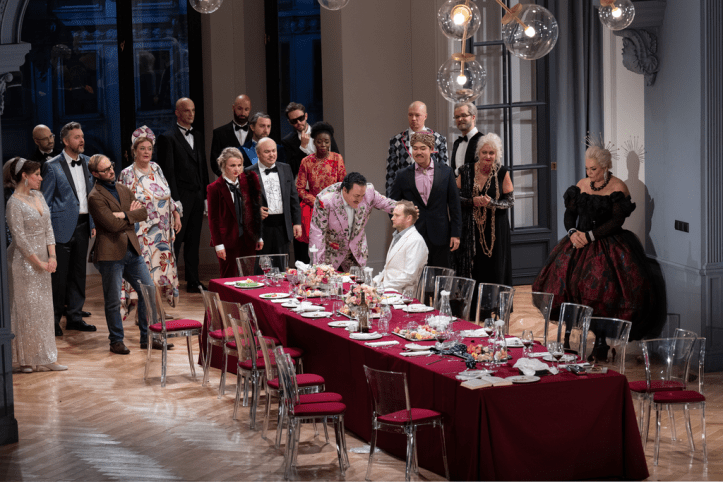

In a similar vein, De Munt – La Monnaie revived Dmitri Tcherniakov’s staging of The Tale of Tsar Saltan. This was a similarly unforgettable evening. The house orchestra was once again on staggering form, technically beyond reproach. The cast, throughout, was excellent. But it was Bogdan Volkov’s performance as Gvidon that was simply astounding. This is an assumption of a role that will define his career. Tcherniakov sets the action as the imaginings of a young autistic man who lives through fairy tales. To see the images he paints in his mind come to life in backdrops on the stage through real-time animation, was so moving – particularly so at the end of Act 2, with music emerging from all over the auditorium bathing us in sound, and images taking shape on stage from initial lines into vibrant views. This is a staging full of humanity, one that abounds in detail and imagination, and it was superbly performed by everyone on stage and in the pit.

This has been a very full year of opera going, with much satisfaction along the way – together with some rather less satisfying shows, but that is always part of the course. I’m looking forward to seeing what operatic 2024 has in store. In the meantime, I’d like to take this opportunity to wish you all the very best for the year ahead and many happy operatic adventures. Bonne année.