Verdi – La forza del destino

Donna Leonora – Anna Netrebko

Don Carlo – Ludovic Tézier

Don Alvaro – Luciano Ganci

Il Marchese di Calatrava – Fabrizio Beggi

Padre Guardiano – Alexander Vinogradov

Preziosilla – Vasilisa Berzhanskaya

Fra Melitone – Marco Filippo Romano

Curra – Marcela Rahal

Un alcade – Li Huanhong

Mastro Trabuco – Carlo Bosi

Un chirurgo – Xhieldo Hyseni

Coro del Teatro alla Scala, Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala / Riccardo Chailly.

Stage director – Leo Muscato.

Teatro alla Scala, Milan, Italy. Friday, December 13th, 2024.

This new production of La forza del destino opened the 2024 – 25 season of the venerable Teatro all Scala earlier this week, as is traditional on December 7th. The casting of the role of Don Alvaro has been something of a movable feast, with the originally-cast Jonas Kaufmann renouncing his appearance earlier this fall. He was replaced by Brian Jagde (pictured) who withdrew this evening due to an impending happy event, with Luciano Ganci, himself due to take the role later in the run, appearing tonight. The staging was confided to Leo Muscato, with house music director, Riccardo Chailly, leading from the pit.

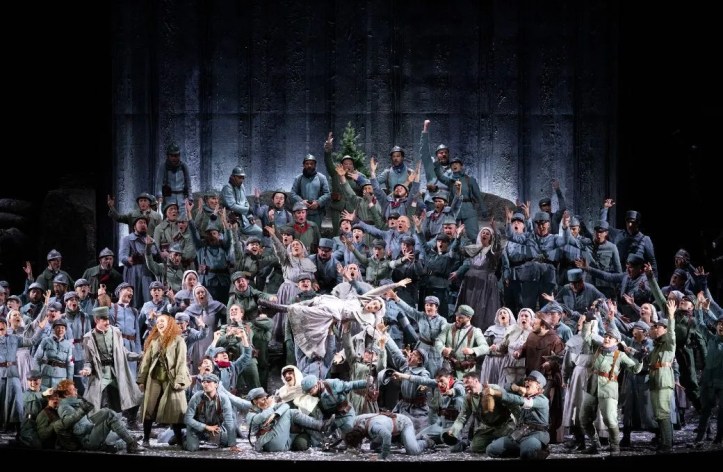

Muscato gives us an intriguing staging. On surface level, in the earlier acts, one might think it rather picturesque. The costumes, by Silvia Aymonino, were initially historical in nature. Yet it became instantly clear that Moscato had something deeper in mind. As Donna Leonora ruminated in her opening aria, we saw her leaving her bedroom to walk through a field of soldiers standing still. The revolving set, by Federica Parolini, kept moving, suggesting that Leonora had no opportunity to control her fate. Indeed, this idea of unchangeable destiny was a consistent figure of Moscato’s staging. For each act, the action developed through a different historical period – Act 3 appeared, from the costumes, to be taking place during World War 1, while Act 4 saw a modern-day population begging for water. I found this a compelling idea, that of a story that transcended time, reinforced by the revolving stage adding a circular nature to what we saw, reminding us that vendettas go around in circles until they find resolution. That resolution, of course, could only be found in the closing pages with the demise of two of the main characters.

Personenregie was fairly conventional. The revolving stage meant that there was continuous action for the principals, even if they were only parked on stage to emote to the front. The chorus was also generally parked on stage, although they were invited to gyrate on occasion. Moscato does give us some very striking stage pictures. The way that Leonora entered a crypt under an altar at the end of Act 2, the stage covered in threatening-looking monks, was particularly memorable. As indeed, was the way that she emerged out of the ruins of a building in a simple white dress to intone ‘pace, pace’ hieratically. Moscato’s staging may initially feel quite conventional, but it does what it needs to do and provides a cogent framework for the action. It might not give us any particularly new insights, or make us consider the deeper implications of the work, but Moscato tells the story clearly and it looks good.

Musically, the chief glories of the evening were Chailly’s conducting and the playing of the Scala orchestra. From the very first measures of the sinfonia, Chailly injected the music with turbulent drama of the kind that promised a thrilling evening of opera. There was a torment that he found in Verdi’s pulsating lines, that sense of uncontrollable destiny that just pulled me in, in the most physical way. His tempi were relatively swift, reinforcing that sense of events overtaking the characters, and he encouraged a thrilling precision of articulation from his musicians. This was a reading full of drama, the constant sense of fate present, for example, in the threats of the lower strings in the big Alvaro/Carlo duet in Act 3, or the heavy brass chords in the closing scene. The Scala orchestra played with terrific verve for their chief. There was a glorious lyricism in the wind playing that found a genuine beauty in Verdi’s writing. There were the occasional passing moments of sour string intonation, but otherwise this was as good as it gets in terms of orchestral playing. The chorus, prepared by Alberto Malazzi, had a very good evening. The tuning of the tenors and basses in ‘La Vergine degli Angeli’ was superb, anchored by very resonant basses, while later the mezzos were delightfully full and piquant of tone. There were a few ragged entries as we went through the evening, but generally the chorus has consolidated the considerable improvements they have made since Malazzi’s appointment.

To be charitable, I would assert that Anna Netrebko’s Leonora was suffering from an unannounced indisposition. To be frank, I would suggest that this was not the quality of singing I would expect at this address. The voice seems to be curiously produced, seemingly throaty and being made to be artificially bigger. This meant that support did not sound lined up, and it also meant that her tuning was not suitable for those of a sensitive disposition. Her intonation throughout lacked accuracy, with intervals not judged cleanly. Moreover, her singing lacked sheer beauty and warmth of phrasing, although the text was clear. Often one might see a performance where vocally the artist might not be on top form, but compensates for this with sheer musical understanding. This was not one of those, even though Netrebko’s commitment was not in doubt and she gave generously of herself. She appears to have three separate instruments: a matronly chest register, a middle that lacks support, and an occasionally radiant top. This meant that she did manage to float a decent, soft high B-flat in ‘pace, pace’, but the final, climactic B-flat was not able to be sustained. She was, however, warmly received by her fans, who were very present tonight.

Ganci showed us what real, Italian lyricism should sound like. His singing was filled with sunny tone and he made a genuine effort to sustain dynamics and shade the line. The top did threaten to succumb to gravity, lacking some spin and the ability to support the higher-lying lines. And yet, he showed that kind of implicit stylistic understanding and ability to make the text really mean something that one would expect to hear on this stage. His was a thoughtful, almost dreamy Alvaro, finding a real poetry in his big aria, precisely due to his ability to shade the line.

I was delighted to see Ludovic Tézier on terrific form after his disappointing Scarpia in Rome back in October, where he was severely hampered by the acoustic. His baritone tonight was in glorious shape, ringing out into the room with seemingly unlimited power. The top opened up thrillingly, yet he also sang with an impeccable legato and breath control that made the endless phrases seem like a walk in the park. Naturally, Tézier also brought significant textual awareness to his singing, always filling the words with meaning. His duets with Ganci gave much pleasure.

Vasilisa Berzhanskaya sang Preziosilla with the agility one would expect of a Rossini singer. She also gave us the trills in her ‘Rataplan’ that so many before her have not been able to manage. She was a vivacious stage presence. Unfortunately, the voice lacks amplitude, a size or two too small for a house as large as this, and she was not always optimally audible. Audibility was not a problem for Alexander Vinogradov’s Padre Guardiano. His bass was big and resonant, even if his Italian was rather exotic in flavour. Marco Filippo Romano was an extrovert Fra Mellitone, making so much of the text, while Fabrizio Beggi made much of little as the Marchese di Calatrava. Carlo Bosi was a nicely, characterful Mastro Trabuco, the tone bright and forward. I was also impressed by Marcela Rahal as a sunny-toned Curra and Xhieldo Hyseni in the tiny role of the Chirurgo, with a wonderfully warm and rounded bass – a name to watch.

At its best, this was an evening that was full of drama and excitement. Chailly and his orchestra were simply thrilling, Moscato’s staging was clear and intriguing, while Ganci and Tézier both gave pleasure. Unfortunately, the evening was let down by the Leonora who gave us singing that did not compensate for the technical issues with interpretative insight. That said, Netrebko was very generously received by the audience at the close and throughout the show, and applause this evening was generous and warm for the entire cast. Certainly in the orchestral playing and Chailly’s conducting, as well as the singing of the leading tenor and baritone, we had an evening worthy of the house.

[…] but it was Verdi who was most prominent in my operagoing this year. The year ended with a Forza del destino at the Scala, notable for the magnificent playing of the Scala orchestra and Riccardo Chailly’s […]

[…] was not at the level I know they’re capable of, following their thrilling playing in December’s Forza del destino, with string intonation frequently rather raw. That said, the horn playing was notable for its […]